Nazi documents on a forced sterilization at the Dachau concentration camp, Gestapo index cards, the notebooks of an anonymous Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust and Stars of David from the Buchenwald concentration camp.

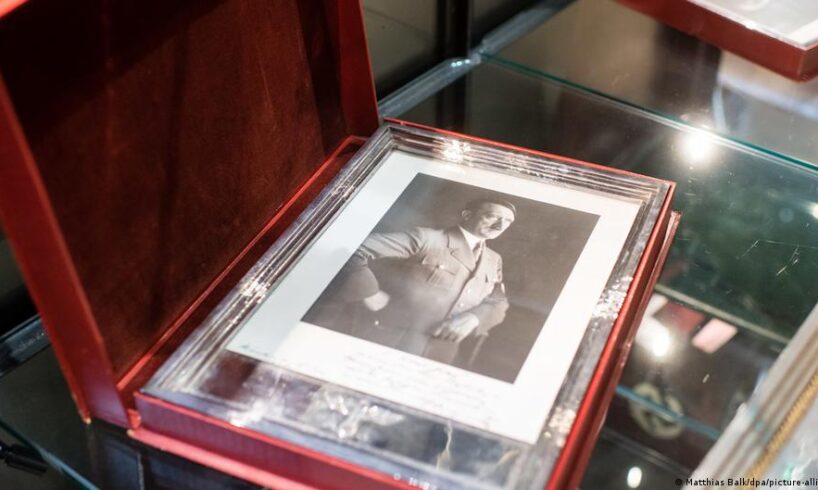

These are just some of the items that were due to be sold at the Felzmann auction house in the western German city of Neuss this week before it was cancelled following public outcry. Many of the objects dating from 1933 to 1945 up for sale under the title “System of Terror Vol II” contained the names and personal information of the persecuted.

“For victims of Nazi persecution and Holocaust survivors, this auction is a cynical and shameless undertaking that leaves them outraged and speechless”, Christoph Heubner, the executive-vice president of the International Auschwitz Committee said in a statement. “They should be displayed in museums or memorial exhibitions and not degraded to mere commodities.”

“Something like this is simply not appropriate, and it must be clear that we have an ethical obligation to the victims to prevent such things,” Germany’s Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul said. He also called for a complete ban on the commercial sale of such items in Germany.

Blanket ban on sale of Nazi artifacts ‘unworkable’

Auctions of Third Reich artifacts have happened in Germany before, and dealers are easy to find online. That’s because a blanket ban would be legally unworkable, according to Leipzig-based lawyer Peter Gischke.

“It’s insufferable, but it’s not a criminal offense to even consider such a despicable act. No criminal law in the world could prevent that,” Gischke told DW. “When our foreign minister says, for understandable reasons, that all of this must be banned, that’s all well and good, but what exactly do you want to ban? Do you want to ban every letter written between 1933 and 1945?”

The typewriter on which Adolf Hitler typed parts of “Mein Kampf” was auctioned for 125,000 DM (€64,000) in Munich in 1987Image: teutopress/IMAGO

According to Section 86 of the German Criminal Code (StGB), it is prohibited to distribute, produce trade or make publicly available on data storage devices — which includes books —propaganda material from unconstitutional organizations in Germany. The law applies to propaganda material, such as swastikas and the SS Totenkopf (skull) insignia, issued by any banned organization, whether from the left or the right of the political spectrum, with certain exemptions for use in artworks or educational contexts.

It specifically forbids the distribution and display of propaganda materials that are intended to continue work toward the aims of the National Socialist regime, in particular flags, badges, uniform parts, slogans and forms of greeting such as the Sieg Heil or “Hitler salute.” Items decorated with Nazi symbols may be sold but the symbols themselves must be taped over or pixelated in case of online sales.

“Distribution — and distribution is a broad term — also includes hanging a Nazi flag in my living room and inviting 20 people over for a cozy evening, because then I am distributing a Nazi symbol, which is indeed prohibited in Germany,” Gischke explains.

While having a copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf on your bookshelf is not a criminal offense, printing multiple copies and selling them at a local flea market certainly is. Such cases can be reported to the police and documented by any member of the public.

For sale: Hitler’s wristwatch and Harry Truman’s letters

Similar legislation on the sale of Nazi memorabilia exists in Austria, France and Hungary. But in the US and elsewhere, it’s pretty much a free market. It is difficult to ascertain exactly how big the market is, but demand is growing, at least according to Bill Panagopulos, the owner of Alexander Historical Auctions in Maryland.

While major auction houses such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s refuse to handle such artifacts, Panagopulos’s auction house hit the headlines in 2022 over the sale of a gold wristwatch believed to have belonged to Adolf Hitler and a dress worn by Eva Braun, Hitler’s wife. Despite outrage from Jewish leaders from the European Jewish Association, who described the auction as “an abhorrence,” the watch sold for $1.1 million.

Panagopulos acknowledges that he’s “taken a lot of flak” over the years for his work, but he refutes “the common accusation that people are profiting from the Holocaust.”

He believes that the auction in Neuss should have gone ahead, if only to prevent the artifacts from disappearing altogether.

“For them not to be sold in a public forum, I consider it a crime in itself because it makes that material unavailable to the family, to scholars, unavailable to institutions,” he told DW. “I’d rather not make a profit from it but I’d rather not see it sold under the table, you know, or thrown in the rubbish bin.”

In 2022, Adolf Hitler’s wristwatch sold for $1.1 million at Alexander Historical Auctions in the USImage: Alexander Historical Auctions

Panagopulos’s father comes from the village of Kalavryta in Greece where Nazi troops massacred hundreds of men and boys over the age of 14. The women and children were rounded up and locked in a local school that was then set on fire but were able to escape. He says he has a framed document with a rare signature from Karl von Le Suire, the Nazi general who ordered the massacre and Wilhelm Speidel, the Nazi military commander of Axis-occupied Greece at the time. For Panagopulos, it’s a “reminder of crimes gone past.”

Most items of historical significance are sold to Jewish buyers, he claims. When asked about whether he sees a link between growing right-wing extremism and the apparently expanding market for Third Reich artifacts, he says that neo-Nazis are “too stupid and too poor to buy this type of material and they don’t want it.”

The stereotypical billionaire buyer with a dark fetish is also more of a myth, he says.

Panagopulos sells anything and everything of interest to collectors, including artifacts of slavery such as shackles and bills of sale, as well as Confederacy swords and flags from the American Civil War. The most popular items relate to the First and Second World Wars, the Vietnam War, and to a lesser extent the Korean War. The real high value lots are what he calls “content material,” objects of major historical significance.

“You can buy a letter from Harry Truman that says, ‘Thank you for the smoked fish,’ which is very boring and it will sell for $120. Many years ago I sold a letter from Harry Truman explaining why he decided to drop the bomb on Hiroshima, and I sold it for $20,000,” he explains.

Researchers trawl eBay and flea markets

Fritz Backhaus, a historian and director of collections at the German Historical Museum (DHM) in Berlin, understands the outrage over the sale of Third Reich artifacts very well. In his opinion, these things belong in public institutions where they can be properly researched, preserved and presented in the proper context.

“It’s a really important discussion that has now been started concerning which ethical, legal and academic questions are connected to the trade in objects from the Nazi period, in particular objects from victims or those that reflect their fate,” Backhaus told DW. “The question is always one of background and the provenance of the object being offered. Were they obtained unjustly, is there any information about how the person who is donating the piece came to own the object?”

The myth of Germany’s post-Nazi ‘zero hour’ explained

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Most Third Reich artifacts in the DHM have been donated by members of the public, Backhaus says. When the Third Reich collapsed, German society was saturated Nazi propaganda and in the immediate post-war period, much of it was either destroyed or hidden away. But Backhaus says that since the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, more and more items keep surfacing as attitudes towards how best to deal with Germany’s dark past change.

Researchers at the museum like to keep an eye on auction catalogues and upcoming sales ready to purchase items of particular historical relevance to their collections.

“It’s hard for us to keep track though because there’s such a big market of material on offer, for example on eBay and at flea markets,” he said.

Discussing the market for these types of objects, Backhaus says that “there’s both a fascination with evil, and for some, a certain admiration for National Socialism in right-wing extremist circles.”

He also mentions a major purchase by the DHM from the son of Wolfgang Haney, a man whose Jewish mother survived the Holocaust in hiding and who had made it his mission to purchase as much Third Reich antisemitic propaganda as possible in order to donate it to research institutions.

‘I’m less excited when someone finds Hitler’s toothbrush’

Thomas Weber is a professor of history at Aberdeen University in Scotland and the author of Becoming Hitler: The Making of a Nazi. He says that though he would much prefer it if people would do the ethical thing and donate to public institutions, he isn’t sure that introducing a total ban “would produce the result we’re all hoping for.”

“The unintended consequence of a ban is not that suddenly that kind of market will totally dry up […] you run the risk that this material will actually just disappear for good in the wrong channels,” he told DW.

By 1945, German society was saturated with Nazi symbols, iconography and propaganda materialImage: imageBROKER/our-planet.berlin/IMAGO

Motivations differ from person to person, Weber says. For some it’s a hobby in the same way that people collect stamps and Astin Martins. There’s the thrill of the hunt, which Weber likens to Indiana Jones searching for the Holy Grail.

“I also get very excited when I find in private hands, as I sometimes do, new documents, but I’m less excited when someone finds Hitler’s toothbrush or Göring’s lederhosen or this last week with all the news about Hitler’s DNA, this kind of obsession about micro-penises and so on, that is something that I just find really irritating,” he says.

The world’s largest collection of Nazi memorabilia is said to have been amassed by British multi-millionaire Kevin Wheatcroft. His private collection includes Panzers and the door to Hitler’s prison cell in Landsberg where he wrote Mein Kampf. Wheatcroft even claims to sleep in the Nazi dictator’s bed.

Edited by: Sarah Hofmann