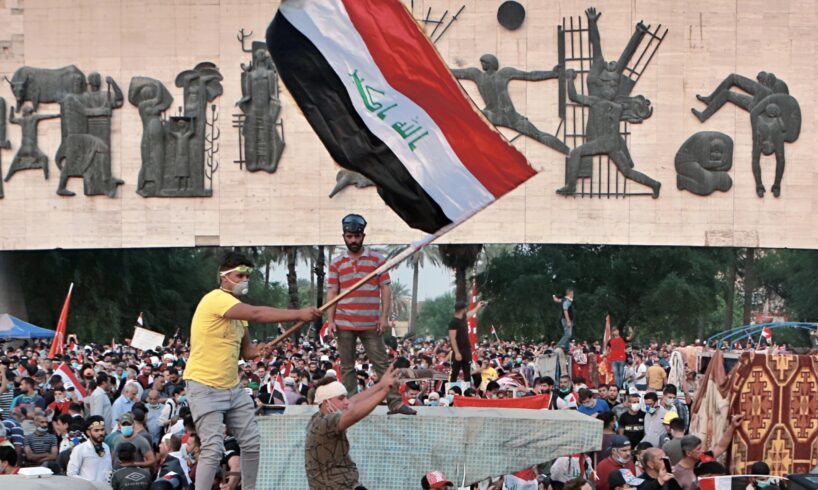

(Photo:Khalid Mohammed/AP)

The outcome of Iraq’s parliamentary election in November revealed extremely poor results for parties and coalitions associated with the largely secular 2019 Tishreen movement. While some factions chose to boycott the vote, citing an uneven playing field due to the massive political spending by establishment parties, three electoral lists aligned with Tishreen opted to contest the election. But together, they managed to secure only a single parliamentary seat. This is a stark contrast to the 2021 election, when the leading Tishreen party, Emtidad, won nine seats, and dozens of independent candidates also entered parliament.

The conventional explanation for this collapse points to parliament’s decision to reintroduce the old electoral law. In 2019, responding to demands from Tishreen demonstrators, parliament replaced the proportional representation system (PR) with single non-transferable vote (SNTV) and reduced the size of the voting districts. These changes were presented as a concession to the protest movement, whose supporters believed it would improve their chances of competing against well-funded establishment parties. As with any electoral system, SNTV had both advantages and drawbacks. While it enabled greater political inclusion by lowering barriers for new entrants to win seats, it also produced a highly fragmented parliament, with more than 30 parties and coalitions, and nearly 40 independent MPs represented in parliament, contributing to legislative gridlock.

In 2023, parliament voted to revert to the previous PR system, to the dismay of smaller parties and independents. Many of these parties including those aligned with Tishreen chose to form broader coalitions in an attempt to enhance their electoral chances, while several MPs decided to join the larger, more established coalitions. Despite their efforts, only a handful of candidates that identify with the Tishreen movement secured enough votes to win seats in the new parliament.

On the surface, the poor results seem to confirm that the system change undermined Tishreen-aligned groups, but a closer look at the election data paints a more nuanced and ultimately different picture. Across several cases, the evidence suggests that their collapse had less to do with electoral design and far more to do with the failure of these parties to maintain relevance and resonance with voters.

A close look at Emtidad is a case in point. The party was mired in internal disputes including a leadership crisis almost from the moment it entered parliament following the 2021 election, and it had effectively collapsed as a political entity before the end of the parliamentary term. This was despite holding 15 seats in parliament following the Sadrist withdrawal in 2022, making Emtidad the sixth largest bloc in parliament. Emtidad did not compete as a party in last month’s election and four of its MPs, including its leader Alaa Al-Rikabi, chose not to run either. Of the remaining eleven who did contest the vote, only one sitting MP retained his seat, and he did so under the banner of Ishraqat Kanun, another grassroots party that emerged in 2021. The other ten MPs lost despite joining large coalitions including Prime Minister Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development Coalition, which theoretically should have given them a good chance of retaining their seats.

What explains their failure to win is the collapse in their voter base. In 2021, the eleven Emtidad MPs collectively secured around 170,000 votes. This time, those same MPs received fewer than 26,000 votes. The drop was even more dramatic for certain candidates. Dawood Al-Taie, one of the highest vote-getters nationwide in 2021 with over 41,000 votes, received just 1,800 in this election. Another candidate, Hamid Al-Shiblawi, who had won nearly 16,000 votes in Najaf four years ago, secured just over 1,000 votes despite running with the prime minister’s coalition.

These details reinforce the argument that the electoral system was not the primary cause of the collapse. Electoral systems shape how votes are converted into seats, but they do not significantly impact a candidate’s ability to attract votes in the first place. The fact that only 15% of voters who backed Emtidad MPs four years ago were willing to do so again requires a deeper examination of what went wrong.

A second telling example is the combined performance of the Tishreen-aligned lists that competed this cycle. Three main entities ran: the Badeel Alliance led by former Najaf governor Adnan Al-Zurfi, bringing together thirteen small parties including the Iraqi Communist Party; the Fao-Zakho Assembly led by former transportation minister Amir Abd Al-Jabbar; and the Civil Democratic Alliance composed of a group of secular activists and public figures.

Only Abd Al-Jabbar was able to win a seat. Even if this election had been contested under the SNTV system, the outcome would have likely been equally disappointing, because a close look at the data indicates that these coalitions failed to field candidates capable of attracting votes. In the eight provinces where they collectively competed and fielded hundreds of candidates, only nine were able to surpass 3,000 individual votes. The vast majority secured only a few hundred votes, or even less.

Abd Al-Jabbar’s 22,000 votes in Basra, up from 7,000 in 2021, reflected his public persona, driven largely by his outspoken stance over the Khor Abdullah dispute with Kuwait, an issue that resonates deeply among residents in Basra. By contrast, Sajad Salim, a prominent and fiercely outspoken MP running with the Badeel Alliance, failed to win a seat, dropping from more than 10,000 votes in Wasit in 2021 to under 3,000 this time.

Without more granular voting data, including demographic details, it remains difficult to definitively explain why their voter base collapsed. One possibility is that their supporters boycotted the election out of disillusionment with the reversion to the old system. But a final example complicates that argument: the case of Ishraqat Kanun.

Although Ishraqat Kanun is not affiliated with the Tishreen movement, it emerged around the same period and cultivated an organic base in the Shia mid-Euphrates heartland, particularly in Karbala and Babil. The party won six seats in 2021, and despite the shift back to proportional representation, it was able to consolidate its gains and increased its seat share to eight. More striking was its ability to expand its voter base. The party doubled its total votes from around 100,000 in 2021 to roughly 200,000 this time. Nor did its incumbent MPs experience any meaningful decline in their personal vote tallies. In fact, one Ishraqat Kanun MP running in Karbala, Mohammed Al-Ali, increased his vote count from 12,200 in 2021 to around 17,600 this time around. Ishraqat Kanun’s performance demonstrates that under the same electoral system that supposedly disadvantaged small parties, it was possible not only to survive but to expand, provided the party had organizational discipline, a clear identity, and sustained engagement with voters.

Taken together, these cases suggest that explaining the collapse of Tishreen-aligned parties requires more than blaming electoral engineering. Their 2021 momentum was built on a platform of a repudiation of the ruling elite, but that message appears to have not resonated sufficiently to mobilize voters in 2025. This could reflect disillusionment among supporters with the performance of their MPs, or a failure by these parties to manage the expectations of their base. What these movements cannot do is replicate the political platforms of establishment parties, which rely heavily on rent-seeking, patronage, and clientelism to maintain their base. Not only do they lack the resources and networks to compete on those terms, but any attempt to do so would undermine the principled foundations of their original appeal.

A new approach will be required, one that demonstrates organizational competence, policy seriousness, and integrity rather than relying solely on protest-era slogans. Ishraqat Kanun’s success suggests that such a model is possible, even for newly emerging parties. Whether Tishreen-aligned forces can learn from these lessons will determine whether they remain a political footnote or re-emerge as meaningful actors in Iraq’s evolving landscape.