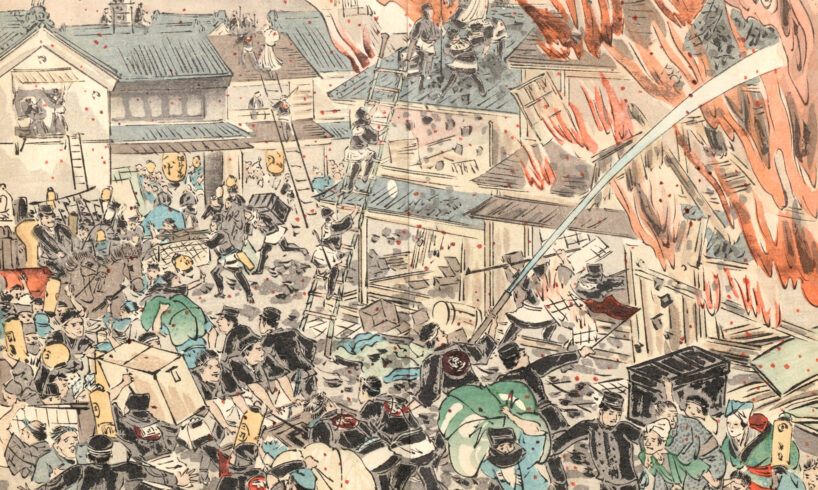

The Great Fire of Meireki in 1657 was one of the worst disasters to ever hit Edo (modern-day Tokyo). The blaze destroyed 60% of the city, including the keep of Edo Castle, and killed around 100,000 people. The horrors did not end once the flames were put out, though, as armed gangs roamed the streets and terrorized the remains of Japan’s capital in the aftermath of the apocalyptic event.

The city eventually rebuilt and order was restored. To keep it that way, a new kind of police force was created. They eventually called themselves the Arson & Armed Robbery Investigators (Hitsuke Tozoku Aratame Kata), but what they actually were was a Japanese samurai SWAT team.

Print depicting the impact of fire on the wooden buildings of Edo. Artist unknown.

Hitsuke Tozoku Aratame Kata’s Arsenal

There were fewer than 300 samurai cops during the Edo period, policing half a million people. It was preferred that they didn’t kill criminals, because executions before a torture-obtained confession was considered bad form.

As samurai, Edo law enforcement officers had the right to carry swords, but their primary weapons were nonlethal, such as the jitte truncheon or the sasumata polearm restrainer, still very popular among modern Japanese police (and the occasional jewelry store employee).

The reason they managed to keep Edo relatively at peace was because they were aided by a network of helpers, spotters, informants… and cops with license to kill: the Hitsuke Tozoku Aratame Kata. Known more commonly as Kato Aratame or just Kato, this was a paramilitary unit created to combat the most serious crimes in and around the city.

Unlike the forces of the Machi-bugyo (Edo’s high-court judges, mayors and chiefs of police), the Kato’s arsenal was almost nothing but lethal weaponry, starting with swords and later even incorporating rifles. They still carried the jitte, though, as those were Edo-equivalents of police badges.

Hitsuke Tozoku Aratamekata was an elite force. Sourced from the shogun’s personal vanguard, there were only about 50 of them, and the vast majority were responsible for paperwork like filling out reports or delivering subpoenas. But because they were a small, highly trained, highly organized group, they could move with lethal efficiency as a mobile strike team against groups of organized criminals.

The story goes that their blitzkrieg breaking up of a gang led by one Aoi Kozo, a repeat robber and rapist, resulted in his sentencing and execution just 10 days later.

Samurai Kojima Yataro depicted holding a severed head. By Utagawa Kuniyoshi (c. 1853) | Wikimedia

Samurai With the Authorization To Terrorize

While technically all samurai had the right of the kiri-sute gomen (being able to kill anyone of a lower social position), it was a bureaucratic maze with legal caveats and post-slashing investigations and serious repercussions if it was decided that the killing was unjustified. The Kato were given blanket permission to not worry about that.

They didn’t have the authority to officially execute a captured suspect (though they could legally beat them), but if they felt that their life was in danger, lethal force was fully authorized. There were, however, drawbacks.

While the group had some successes, there were many more accusations of false arrests and coerced confessions. Since the Kato were much smaller than even the already-understaffed regular police, they relied more heavily on rumors, hearsay and criminal informants.

Once they acted on information, they kind of just assumed that they got it right and that was that. No further investigation was necessary. The amount of legal leeway the Kato got fostered an atmosphere of the samurai SWAT members feeling like they were always automatically in the right.

Soon, the Arson & Armed Robbery Investigators gained a reputation for excessive brutality, especially when it came to interrogations, which were reportedly more violent than those employed by the Machi-bugyo apparatus.

You also have to keep in mind that during the Edo period, a samurai cop who couldn’t get a confession out of a suspect was perceived as not putting their heart into their job. You have to wonder how far the Kato went to be labeled as “excessive” by the standards of their times.

A 1875 print in the Yubin Hochi Shimbun, showing Ninsoku Yoseba prisoners teaching themselves to read. By Yoshitoshi Tsukioka.

Hasegawa Nobutame: Kato’s Good Cop

The Hitsuke Tozoku Aratame Kata were at times led by some truly terrifying people. One of their early leaders, Nakayama Kageyu, was so feared for his violent methods (including a new kind of torture-restraint he devised himself) that he earned the nickname “The Demon Investigator.” But, the reason why the Kato aren’t universally remembered as a bunch of sadistic, government-sanctioned criminals is all thanks to one man: Hasegawa “Heizo” Nobutame.

He was the head of the Kato from 1787 to 1795, and was the one responsible for bringing Aoi to justice, alongside many other criminals. While he was stern when it came to the law, he also led with compassion and humanity, and recognized that Denmacho, the city’s prison from hell, did a poor job in terms of rehabilitation.

To remedy that, Hasegawa became the overseer of the Ninsoku Yoseba, a government workhouse where vagrants and ex-convicts were taught carpentry, joinery, lacquerwork and other trades that might help them find gainful employment and reintegrate into society. The residents of the facility also received wages and time off.

Hasegawa most likely wasn’t the one who came up with the idea, yet he was a big supporter of it. That doesn’t make him some kind of radical reformer, but a man who believed that not all criminals were beyond redemption. He was arguably as close to a good cop as you could get in 18th-century Japan.

Related Posts

Discover Tokyo, Every Week

Get the city’s best stories, under-the-radar spots and exclusive invites delivered straight to your inbox.