Not that long ago, most people truly believed that watching over them was an all-knowing deity who was privy to their innermost thoughts and kept track of everything they did down here on earth. Though in Western countries sceptics have succeeded in reducing the power and influence of the priesthood who assured them a benevolent God was looking after them, most men and women feel uncomfortable with the idea that life has no meaning and it is useless to seek one. As far as they are concerned, what some – channelling Blaise Pascal – call “the god-shaped hole” has to be filled with something that is at least credible.

This presumably is why in some parts of the Western world there are signs that Christianity is enjoying a modest revival, with pews that until recently had remained empty being occupied by young people looking for a system of values that is more meaningful, less evanescent, than the largely hedonistic or consumerist ones that are typical of modern societies. Religious faith may be irrational, but it does give people something that is apparently solid they can hold on to, which is more than can be said for the often murderous political cults that, for over a century, gave many millions of individuals the sense of community they craved but which, as time passed, were found wanting.

Despite such failures, attempts to replace traditional deities – among them the Judeo-Christian God, the Islamic Allah and the countless members of the Hindu pantheon – with something that is more up to date are still being made. The ecologically-minded have their “mother nature” or Gaia, and some have devised ceremonies, based on pre-Colombian, Celtic or Shinto practices in which they worship her.

And then there are many people of a progressive disposition who, while they tend to be keen on ecology, think the salvation of humankind lies in the hands of “the science” to which they constantly refer because, in their view, it must have an explanation for everything that matters.

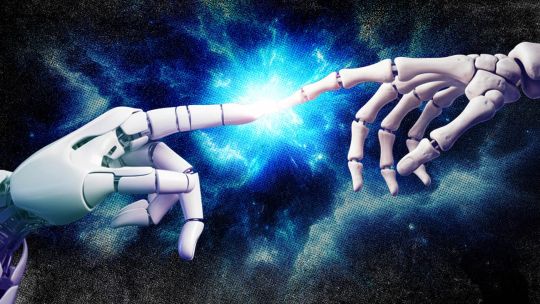

“The science” has recently spawned Artificial Intelligence, an omniscient entity that, if the enthusiasts are right, fully deserves the capital letters that regularly adorn it. Unless the prophets of AI have it wrong, the world is moving towards a strange theocracy in which a descendant of the French Revolutionary Goddess of Reason will hold sway.

Those who are pushing it confidently predict that in the next few years AI will transform our planet by providing quick, definitive and ruthlessly logical answers to almost all important questions and we had better get as used to obeying its orders as our fathers were to obeying those sent down by almighty God as interpreted by His anointed representatives here below. They also seem to take it for granted that the country that first gets its hands on Artificial Intelligence will rule the world, which is why the two main contenders, the United States and China, are investing colossal amounts of money in developing the hardware and software it will need.

Is any of this realistic? Many financiers are coming to the conclusion that the AI boom that is rattling stock markets will share the fate of previous splurges like those that, over the years, were interrupted or even ended by busts that ruined not just those who had put large sums of money into them but also a great many others. Fall-out from the subprime housing market crash of 2008 can still be felt in many parts of the world where the incomes of low-paid workers have yet to recover. Doom-mongers fear that, thanks in large measure to the allure of AI, something unpleasantly similar could be brewing right now.

In addition to attracting an enormous amount of money and, while about it, gobbling up electric power – by 2030 it will need as much as is currently generated by Japan – the spectre of AI is already having a very strong psychological impact. It could hardly be otherwise. The belief that within a few years it will take over a rapidly widening range of jobs, throwing countless men and women out of work, must weigh on younger people who are already worried enough about their prospects in an unstable labour market. The old days in which you could confidently plan a career that would last decades during which you would climb higher and higher seem to have gone for good. It is now taken for granted that henceforward experience will count for little because every four or five years you will have to abandon what will be regarded as antiquated ways of thinking and learn whatever happens to be in demand.

For evident reasons, most people find this is a most unsettling prospect. So too are the implications behind the belief that AI will provide governments, whether they are rigidly dictatorial like China’s or a bit more democratic such as those in the West, with tools that will enable them to keep tabs on what goes on in the minds of the people they rule.

They may not manage to read all your thoughts, as the gods that once hovered over much of the world were assumed to be capable of doing, but by monitoring your interactions with electronic devices, poring over whatever you post on social media and seeing where the now ubiquitous algorithms lead you, governments will be able to get a fairly accurate idea about what you are thinking at any given moment. In the United Kingdom and other European countries, an allegedly hateful statement posted on the Internet can already land you in jail. In China, even appearing to be slightly unorthodox can see you denied credit facilities and prevented from moving to a neighbouring town. If AI fulfils its promise, this is what is coming our way.

Much is being made of the conviction that AI is now far smarter than any mere human and that before long it will be entitled to look down on its creators much as we do when dealing with farm animals or insects. This belief is having a dampening effect on people who engage in artistic pursuits; they see AI elbowing them aside by churning out countless pieces of music, poems, novels, doctoral theses and the like that are just as appealing as the ones they struggle to come up with. Teachers everywhere complain that students are getting AI to write their essays and suspect that, as it improves, it will be impossible for them to distinguish between the pupils who genuinely want to learn more and those who try to deceive them.

Needless to say, academics are not the only people who see the difference between perceived truth and falsehood shrinking at an alarming rate thanks in large measure to machines that, in theory, should be making it far easier to tell them apart. Many others are every bit as worried, but it would seem there is nothing they can do to force the Goddess of Reason to put an end to her destructive rampage.