It’s a clear morning in late November, and exterminator Kenji Shuto is leading a four-person team down a street lined with Asian bars and eateries close to Tokyo’s JR Okubo Station.

Dressed in matching blue uniforms with white armbands reading “Shinjuku Ward” in black letters, the crew scans the corners of a building entranceway for small black boxes as the owner of a Thai restaurant watches curiously.

Shuto opens the first box. “Unchanged,” he says. A member of the team notes the result as he moves on.

“Empty. This one needs more bait,” he says, prompting another team member to step forward with a plastic bag of brown pellets. As they continue, Shuto receives a call from another crew conducting the same task in a different neighborhood. His team wraps up and heads down the street to repeat the routine. It’s an efficient process — a single patrol usually covers about 10 kilometers and can’t afford delays.

Shuto’s work plays out in the city’s blind spots — in the ravine-like gaps between tightly packed buildings, behind the stone slabs of a centuries-old shrine and in the greenery of pocket parks and apartment blocks. While recent headlines fixate on bears in the countryside, Tokyo has long been dealing with a menace of its own: rats.

With roughly 200 problem spots identified in this corner of the capital, Shuto and his team set bait stations — about 28 centimeters wide, 25 cm deep and 13 cm tall — to cull a growing population of dobu nezumi, or “sewer rats” in Japanese, also known as brown rats.

Workers from CIC (Civil International Corporation) head through the streets near JR Shin Okubo Station.

| JOHAN BROOKS

CIC workers check black boxes placed at spots that rats might frequent in Tokyo’s Okubo neighborhood.

| JOHAN BROOKS

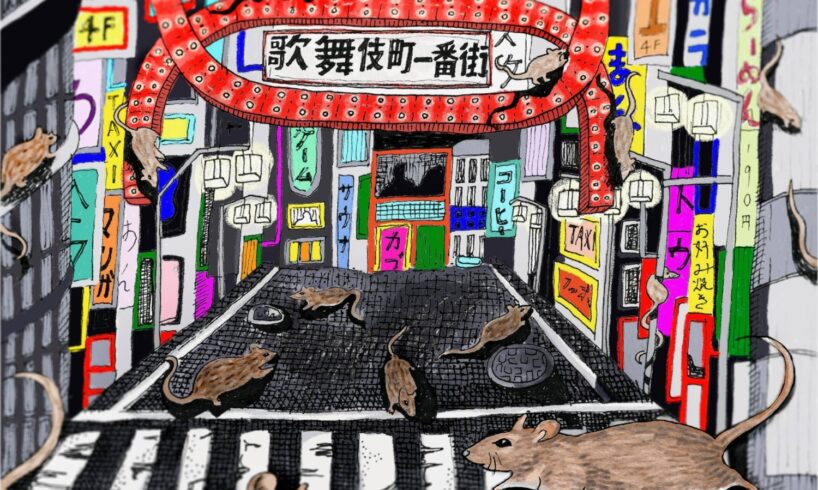

“The bait, which includes sunflower seeds, is carefully mixed and flavored so even those rats accustomed to human food waste will eat it,” says Shuto, 54, a veteran supervisor at CIC (Civil International Corporation), a pest control firm with branches nationwide. It was hired by Shinjuku Ward to oversee its busiest areas: Kabukicho, a nightlife hub, and nearby Okubo and Hyakunincho, both known for their large international communities.

The poisoned bait isn’t immediately lethal. It works only after multiple feedings and poses no threat to humans if accidentally ingested. Once a week, from mid-October to mid-December, Shuto and his crew have been checking the traps, replenishing bait, clearing trash and removing the occasional dead rat.

“When we set up bait stations in Kabukicho, building managers were happy to see the rats disappear, but the effect didn’t last — they came back quickly,” Shuto says. “Poison bait is only a temporary fix. The real solution lies in better waste management.”

The tightly packed streets of central Tokyo are a great place for brown rats to hide.

| JOHAN BROOKS

Rat numbers surged in Tokyo after pandemic-era restrictions were lifted and nightlife and food businesses returned, bringing an increase in garbage with them. Across major hubs such as Shinjuku, Shibuya and Ueno, newly reopened bars and restaurants, many run by inexperienced owners, left trash exposed — a feast for the quick-footed pests.

According to the Tokyo Pest Control Association, rat-related consultations more than doubled over the past 15 years, rising from 1,691 in 2009 to 4,192 in 2024. The pandemic only magnified a problem that had been brewing for years. The post-COVID surge in tourists didn’t help, contributing to the litter and fueling a slew of social media posts that showed just how visible the rats had become.

Sticking to the garbage rules

In 2023, a short clip showing more than 30 sewer rats swarming over a pile of garbage in Kabukicho went viral on social media. The footage — along with a wave of similar posts and complaints — prompted Shinjuku Ward to allocate an extra ¥12.29 million to its supplementary budget to tackle the problem starting in November of that year.

“Previously, most consultations were about roof rats entering homes and how to control them,” says Masahiro Terada, an official in the environmental hygiene section of Shinjuku Ward’s public health division. “But after COVID-19 restrictions were lifted in 2023, brown rats began appearing more frequently, and we started focusing on that issue.”

Kabukicho’s sewer-rat boom is believed to stem from the pandemic-era lull in human activity, which gave rats room to breed. Sloppy trash disposal by some businesses also created reliable feeding grounds. The rodents reproduce quickly: They can begin breeding at around 3 months old, produce six to 10 pups per litter and give birth five or six times a year.

In addition to brown rats, Tokyo also hosts a number of black rats that live in the walls of old buildings and feed off kitchen leftovers.

| LILY PISANO

In Tokyo’s concrete jungle, two types of rats dominate urban spaces. Brown rats, measuring 23 to 26 centimeters long and weighing 150 to 500 grams, favor damp environments such as sewers, garbage disposal areas, underground arcades and food storage warehouses. They nest in damaged sewer pipes, cracks in concrete and outdoor burrows, and primarily feed on garbage and food scraps. Black rats, also known as roof rats, are smaller — 15 to 20 cm and 100 to 150 grams — and live inside buildings, where they climb walls and beams, nesting in ceilings, attics or behind appliances, feeding on kitchen leftovers. While both pose health hazards, the brown rats dashing across streets are most visible to the public.

To counter the surge, Shinjuku Ward hired CIC to set up poison baits at roughly 200 sites in Kabukicho and later around the same number of bait stations in the Okubo and Hyakunincho districts. The measures initially seemed to work — building managers and restaurant owners reported fewer rats. But progress seems fragile. In the second year, officials found that rats were consuming poison bait at roughly the same rate as before, raising questions about how much the population had declined.

“We think that while these efforts can temporarily reduce the number of rats, they don’t solve the problem at its root,” Terada says. “It’s becoming clear that unless people change how and when they put out their garbage, it will just continue to serve as food for them.”

Japan’s trash disposal rules can be baffling, and even more so for immigrants trying to run food businesses. Shinjuku Ward advises placing food waste in covered bins or sealed containers, though how often that actually happens is anyone’s guess.

Open access to garbage from establishments like restaurants and bars provides the city’s rat population with a nightly feast.

| JOHAN BROOKS

Residents and business owners say the problem has long been obvious.

“To be honest, the rats have always been here,” says Toru Kambayashi, an owner of three bars in Shinjuku Golden Gai, a labyrinth of narrow alleys in Kabukicho crammed with tiny bars and eateries that has served as a nightlife hub for more than half a century.

Kambayashi says he takes precautions to keep rodents out of his establishments, but he heard that in one bar, after the previous tenant moved out and a new operation opened in the run-down space, a one-meter section of the ceiling collapsed during business hours.

“The place was showered with rat droppings,” Kambayashi says, incredulously. “The bar was forced to close.”

The wrong kind of viral

Rats aren’t just a problem in Shinjuku. Shibuya, Toshima, Taito, Chiyoda — any ward with large entertainment and commercial districts — sets its own pest-control guidelines. While there are no precise counts, estimates suggest Tokyo is home to far more rats than current pest control measures can meaningfully address, likely numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

And these vermin can turn up in the most unlikely places.

In January, a customer at a Sukiya beef-bowl outlet in Tottori Prefecture posted a photo of a roughly 5-cm rat floating in a bowl of miso soup. The image spread across the internet, and while many first assumed it was fake, Sukiya acknowledged the contamination on March 22 and issued an apology. The chain temporarily closed all its stores.

A big concern for any city is when the rats become so numerous as to contaminate the food supply.

| LILY PISANO

In 2019, a video showed several rats swarming the shelves of a FamilyMart in Shibuya Ward. The convenience store apologized after the clip spread around the world. Before that, a rat infestation at the former Tsukiji fish market made news as the city prepared for its relocation.

Cases where rodents contaminate the local food supply have caused the most concern. Rats spread bacteria as they move through garbage stations, drains and buildings, leading to issues such as mite infestations, allergic reactions — and in rare instances, bites that lead to severe infections.

“Twenty years ago, most of the consultations we received were about roof rats,” says Takeshi Sasaki, a senior official at Tokyo-based pest-control firm Apex Sangyo and a director at the Tokyo Pest Control Association. “Nowadays, while roof rats are still around, we’re seeing a dramatic increase in consultations about brown rats, which live outdoors.”

Because roof rats sneak into buildings, control measures focus on sealing entry points and trapping any that are already inside, Sasaki explains. Brown rats, by contrast, burrow in outdoor vegetation or nest in gaps in concrete floors near garbage areas. Effective control requires placing poison bait in burrows, filling cracks in concrete and soil to block potential nesting sites, clearing alleyways to eliminate hiding spots and managing outdoor waste that provides a steady supply of food.

CIC workers check rat traps in front of an eatery in the vicinity of JR Shin Okubo Station.

| JOHAN BROOKS

Business owners who are new to Japan may not yet know Tokyo’s rules for proper garbage disposal.

| JOHAN BROOKS

“With the surge in foreign visitors, littering has become a problem in many tourist areas,” Sasaki says. “It’s not just tourists — locals also tend to casually toss trash in busy districts. And with far fewer trash bins than in many other countries, people often discard waste in shrubs and greenery.”

But Sasaki believes there’s another reason rats feel unavoidable in the city.

“Brown rats have always been present in Tokyo, but they’re far more noticeable today because people film them on their phones and spread the clips on social media for likes,” he says. “Sometimes, people even go so far as to deliberately feed sewer rats to lure them closer for a good shot.”

My neighbor, the rat

Rodents haven’t always had such a bad reputation in Japan.

In one tale from the eighth-century “Kojiki,” the country’s oldest surviving chronicle of its mythical origins, Oanamuji (later the god Okuninushi) falls in love with Suseribime, the daughter of distant ancestor Susanoo. Susanoo tests him with a series of perilous trials: two nights spent in rooms filled with snakes, then bees and centipedes and, on the third day, retrieving a magical whistling arrow from a burning field.

As Oanamuji struggles to escape the blaze, a nezumi (which can be interpreted as a rat or a mouse) appears and offers a cryptic hint: “Inside is hollow, outside is narrow.” Oanamuji stomps on the spot the rodent indicates and drops into an underground cavity, sheltering until the fire passes. The rodent then returns the whistling arrow in its mouth, allowing Oanamuji to flee with Suseribime and eventually establish a new nation in Izumo.

Rodents are often viewed in a positive way in Japanese mythology, sometimes as messengers of the gods.

| LILY PISANO

“During the plague outbreak in the Meiji Era (1868-1912), the government ordered rats to be exterminated as vectors of the disease,” says Yasushi Kiyokawa, an associate professor at the University of Tokyo and expert on rats. “But in earlier times, Japan was so impoverished that the presence of rats in a household could be considered a sign of affluence.”

Even today, Kiyokawa notes, rodents are revered as divine messengers at certain shrines, including Otoyo Shrine in Kyoto, where their stone likenesses greet visitors.

By studying both laboratory rats and brown rats — the species in its original wild form — Kiyokawa examines how individual animals behave in natural environments. With lab rats, he focuses on pheromone-based communication, the scent cues that convey anxiety or reassurance and help reinforce social cohesion. His work on brown rats centers on neophobia, the avoidance of unfamiliar objects, a behavior that likely helps them evade traps and rodenticides. He also conducts experiments and behavioral observations on colonies living in cities, barns and other real-world settings.

Yasushi Kiyokawa is an associate professor at the University of Tokyo and expert on rats. He is working on ways to better manage the rat population.

| ALEX K.T. MARTIN

“Brown rats are highly intelligent — about as smart as dogs,” he says at his office, pulling up a YouTube clip of rats trained to spin, walk on their hind legs and shake hands. “That’s why they’ve been a problem for humans for as long as we’ve existed.”

Rather than eliminating them entirely, Kiyokawa wants to minimize the damage rats cause while finding ways to live with them as part of a broader ecosystem.

“We want to move away from the idea that a town or district is ‘bad’ just because a single rat is spotted,” he says. “Seeing one on the street doesn’t mean disease will break out.”

One recent evening, a few members of a local business association in Shibuya’s Sakuragaoka district gathered in a room near Kiyokawa’s office for a brainstorming session with other experts and academics. The association had been hosting rat-control workshops and was looking for ways to manage the rodents more effectively.

Kenji Shuto says he can only do so much when it comes to pest control. The real answer lies in better waste management.

| JOHAN BROOKS

Among those in attendance was Tsutomu Tanikawa, director of the Japan Pest Control Association and a doctor of veterinary science who has spent decades on the front lines of rat control.

“In Tokyo, roof rats are declining, but sewer rats are probably on the rise,” Tanikawa says. “They’re hard to manage, and using the same methods repeatedly only leads to an endless game of catch-up. Real progress requires broader community involvement and can’t be achieved by simply hiring a contractor.”

Rats shouldn’t be a target for wholesale eradication, he adds. “They need places to live, just as we need to protect people from harm.”

Considering how many cities around the world deal with rats, some believe it’s time to start looking at solutions that involve living together.

| JOHAN BROOKS

Could success hinge less on traps and poison and more on coexistence? It’s a question Paris — another city long plagued by rats — is now exploring. In 2023, Mayor Anne Hidalgo appointed a committee to explore how humans and rodents might live together safely. Officials examined Project Armageddon, which seeks to manage the rat population and reduce prejudice against the animals while keeping public spaces clean and minimizing health risks.

Researchers at the University of Helsinki are looking into the same idea, framing the relationship between humans and rats as a negotiation rather than a conflict.

It’s a perspective that may prove useful as Tokyo’s rat population shows no signs of abating.

“Rats may cause trouble, but other creatures in the natural food chain depend on them to survive,” Tanikawa says. “If we can accept that some rats will exist and ensure they don’t cause problems, we can build a relationship of coexistence.”