Last month, Southern Weekly reported on a policy at some hospitals in Shanxi requiring that ADHD patients get a “Class 1 Psychiatric Drug Prescribed” stamp in their hukou household registration booklet before receiving pharmaceutical treatment. Numerous patients reported similar experiences, with some finding that hospitals had added the stamp without telling them. Hospitals claimed they were following instructions “from above,” but provincial health authorities told Southern Weekly that they are unaware of any such higher-level requirement. The report emphasized the apparent lack of legal basis for the policy, and quoted lawyers who said that only public security authorities are authorized to issue or modify household registration documents. Public security authorities said patients should be free to refuse the stamp, but appeared to brush the situation off as “a matter between the patient and the hospital.”

Some patients have reportedly stopped treatment, fearing that the stamp could damage their education, employment, or even marriage prospects. Others have resorted to costly or inconvenient workarounds like getting a new booklet issued and using the old one to pick up medications while keeping the other “clean” for other purposes; or making frequent interprovincial trips, paying for a fresh diagnosis each time. One patient quoted in the report asked: “Why do they have to leave this mark? We just have neurodevelopmental differences, we’re not mentally ill. And even if we were, why reinforce the stigma around that?” The parent of another patient commented: “How are you going to be able to explain that it’s just a pharmaceutical administration stamp? People will just think, ‘This kid has a history of mental illness.’”

A handful of articles in recent years from Sixth Tone (before its reining-in) and South China Morning Post have described other challenges facing Chinese people with ADHD, from inadequate diagnostic and treatment capacity, especially for adults, to misconceptions and stigmatization among the public and even medical professionals. Not least of these problems is the fact that the condition is widely known in China as 多动症 duōdòngzhèng, or simply “hyperactivity disorder”—placing even greater emphasis than the English acronym on an aspect of the condition that is often absent, particularly in women. One of the Sixth Tone reports, from 2021, noted that: “In Shanxi, there are only two hospitals able to diagnose and treat ADHD — and neither accept adult patients”:

The tight restrictions on methylphenidate make things even more difficult. In April, China’s health authorities finally added adult ADHD to the official list of conditions for which Concerta can be prescribed. (Before then, all prescriptions for adult ADHD patients had technically been illegal.) But even now, doctors can only prescribe two weeks’ worth of pills at a time.

For working-class patients like Jiang, the two-week limit is a huge problem. Jiang had to travel from Shanxi to Beijing twice a month to pick up his medication — a trip that cost him around 1,500 yuan each time.

“Maybe that’s an acceptable sum for wage earners in big cities,” says Jiang. “But for people like me, who earn just under 6,000 yuan a month, it’s a huge expense.” [Source]

The story describes how Jiang came to face criminal prosecution after resorting to buying medication online, and also found himself regarded as a “drug addict” by colleagues as a result.

The Shanxi hukou stamp requirement is far from a national policy, but for many online critics, it was more serious than just a localized case of bureaucratic overreach. Hanging over it is the still-raw memory of draconian Zero-COVID era excesses—commentator Xiang Dongliang discussed his own lingering anxieties in a recent reflection on the deletion of a post he had written about overzealous Chikungunya-prevention policies; another relatively recent example is the backlash against traffic-safety codes for couriers in Shanghai, which reminded some of COVID-era health codes. On WeChat, “Xiong Taihang” decried the ADHD-stamp requirement as irrational, and warned that even local policy excesses should be vigorously and vocally opposed to stop them metastasizing into broader practice.

I like Shanxi.

On one hand, there’s the extraordinary beauty of its great mountains and rivers, and thousand-year-old architecture.

On the other hand, as long as Shanxi exists among the Four Provinces of Mountains and Rivers [a disparaging neologism referring to Shandong, Shanxi, Henan, and Hebei], those of us from Hebei don’t need to worry about being in last place. This story’s an example.

[…] People with ADHD don’t pose any danger to society, and there’s absolutely no need for a stamp in their hukou booklets. Even much more serious mental disorders don’t get a hukou stamp, let alone ADHD, which can disappear [sic].

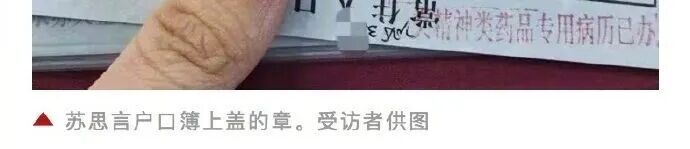

“The stamp in Su Siyan’s hukou booklet. Photo provided by interviewee.”

Even the Shanxi Public Security system was shocked.

A hukou booklet is a document issued by the public security system, and altering its content without authorization is subject to administrative penalties—even detention, in serious cases.

So public security told reporters that patients have the right to refuse the hospital’s stamp.

And when they asked Shanxi health authorities, they responded that they have no such requirement. (I’ll leave it to you to guess whether the hospitals would come up with something like this on their own.)

In the end, one patient trying to get medication came up with a solution: let the hospital stamp her hukou, then once she’d got the medicine, go to the local police station to get them to issue a new hukou booklet.

It’s an absolute farce.

Is this any way to treat people, I found myself wondering?

It’s how we treat pigs, right?

Once the carcass is through quarantine, it gets a stamp with a QR code so it can be traced.

Some officials haven’t got a clue.

No doubt some genius with no background in modern medicine slapped his forehead and thought: “Why would a citizen suddenly develop ADHD? No doubt it means they’re unruly and disobedient. This needs to be controlled, just like Jackie Chan said. We’ll start by controlling access to the medication you need. First, we’ll put a stamp in your hukou ….”

No one should think that if they don’t have ADHD, they can just laugh this off and move on.

People with ADHD pose no danger, which is why they’re the perfect test group.

Lessons learned here will become a model across the system.

Depression, autism, bipolar disorder, hepatitis B, HIV … those will all get you a stamp, and social governance will be ratcheted up.

In the end, they’ll make you wear a six-pointed star to go outside.

[…]

It’s not just government departments authorized to use force that can commit outrages. We’ve already seen this in the past.

Those who’ve experienced the thrill of power feel bereft once it’s gone, and will do anything to get it back.

So when we find discover an injustice, we must react at once, and make some noise.

Say, loudly: “What you’re doing is wrong, what you’re doing is illegal.”

Contact the few media outlets and channels that are still willing to speak up.

Take advantage of the lack of established consensus across the system. Use Department A’s regulations to counter abuses by Department B; don’t wait for Department B to tighten the noose.

Loudly mock ignorant and barbaric new rules, and the people who caused trouble by introducing them.

If our voices are heard by others inside the system, those pushing escalations might encounter opposition from rivals during internal meetings.

It’s fine to want to be an official, but not to resort this kind of nefarious, dirty tricks.

In some less-developed regions of the country, the local cadres are subpar and incompetent. So it’s up to us, the citizens of the nation as a whole, to lend them a helping hand! [Chinese]