The fourth SSPP (Sustainable Smart City Partner Program) Forum convened in Tokyo’s Harajuku district this October at With Harajuku Hall, an open space fostering informal, energetic dialogue.

Launched in 2020, SSPP supports community-building centered on maximizing residents’ well-being, with communities as the main players. The program creates spaces where municipal governments, local businesses, educational institutions and residents cooperate across traditional boundaries.

SSPP provides three foundational initiatives: NTT’s Sugatami platform, offering data that reflect a community’s current state; the Social Designer Training Program, cultivating human capital; and the Co-design Program, working with communities on problem-solving and revitalization. The forum served as a learning space where practitioners shared experiences, insights and challenges.

From program to practice

Local initiatives have shown how SSPP turns ideas into practice. In Nagasaki, the Social Designer program built cross-sector teams that began reshaping urban management. In Oga in Akita, practitioners reframed the narrative that rural areas have “nothing,” showing that vacant or underused places can spark new value. Roundtable discussions deepened dialogue, highlighting SSPP’s essential role in fluid, boundary-less community-building.

Three keynote lectures shared a common insight: Data illuminate the past and present, but the future demands multilayered perspectives focused on human well-being.

Designing change-makers

Miles Pennington, a University of Tokyo professor specializing in design-led innovation, co-director of its DLX Design Lab and the prospective dean of the new UTokyo College of Design, outlined the vision for the college: a five-year bachelor’s and master’s program launching in fall 2027 to nurture change-makers under the motto “See the world through design. Then change it.”

The program will tackle challenges that no single discipline can solve, such as climate disruption, health care access, food security, urbanization and cultural preservation. Students will approach complex issues through multiple lenses — scientific, economic, ethical, cultural — to synthesize design thinking with interdisciplinary knowledge in order to forge essential solutions. Each student will chart an individual path guided by curiosity. “Some of our students may end up working in jobs that don’t even exist yet,” Pennington emphasized.

Change Maker Design Projects in years two and three focus on addressing real-world issues by integrating design skills with a wide variety of academic disciplines. Years four and five will demand “capstone” projects with solutions maximizing social impact. Learning is centered around studios where students can interact with industry partners, other external partners and practitioners to deepen the quality of their projects, and such collaboration may offer potential synergy to further innovation. “We want students to push design’s boundaries,” Pennington said, “to think freely and critically, creating solutions with genuine consequence.”

Data meets passion

Noriyuki Yanagawa, an economics professor at the University of Tokyo, presented “evidence-based policy-making” as essential for moving beyond governance by instinct. EBPM brings transparency to community-building. Digitalization creates opportunities: recruiting diverse talent, executing large projects with small teams and adopting well-being metrics beyond economic indicators.

Yet challenges remain. Vague objectives and ambiguous budgets — the “launch-and-forget” tendency — still plague revitalization efforts. Clear goals and pragmatic data use are essential. Yanagawa’s message: “Don’t wait for perfect data. Start where you can” to build region-appropriate EBPM frameworks.

Data alone cannot drive change. Individual passion, combined with administrative approaches that channel enthusiasm, becomes the catalyst. When these join EBPM’s rigor, regional revitalization gains momentum.

‘Post-demographic urbanism’

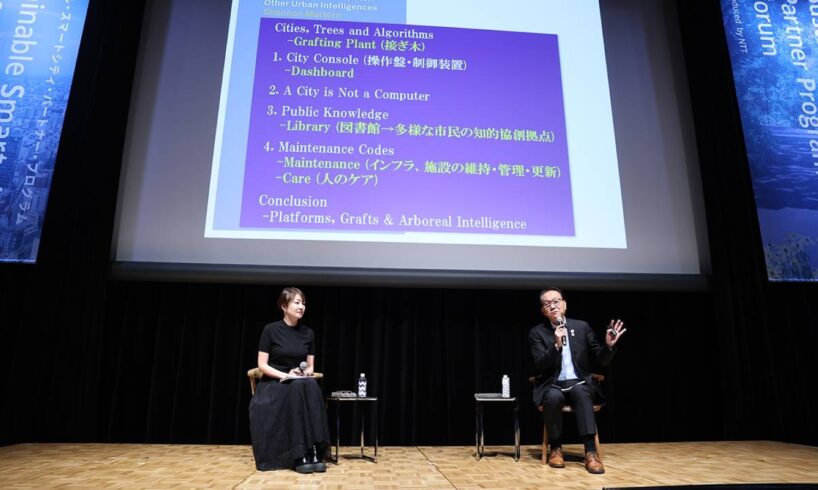

Atsushi Deguchi, a University of Tokyo executive director and vice president, argued that Japan’s rapid population decline demands redefining urbanism as “post-demographic urbanism.” Rather than fixating on statistics, “we need to ask who is actually engaged in cities today.”

“Cities are not machines to be controlled,” Deguchi said, “but living entities shaped by fluid populations.” His metaphor: “Smart cities are like grafting. You must leverage the trunk and pursue the graft,” capturing SSPP’s approach of layering new systems onto existing foundations. This grafting requires five transformations: toward stewardship rather than growth, better use of data, adapting to population changes, making urban forms more flexible, and prioritizing well-being. “These transitions describe precisely what SSPP pursues,” Deguchi emphasized.

Deguchi also stressed that in a post-demographic era, understanding and anticipating regional dynamics demands perspectives that go beyond traditional population-based frameworks. Communities must be viewed through multiple lenses to identify local challenges and latent value, and decision-making must be supported by a platform that integrates such diverse insights. He noted that Sugatami exemplifies this kind of foundation for regional understanding.

Furthermore, Deguchi highlighted the importance of “gradualism” — the willingness to begin acting even when neither the objectives nor the means are fully clear — as a crucial approach for future community-based development. He concluded by expressing hope that SSPP would continue to embody this spirit of gradualism, fostering new pathways for co-creation and community development.

Building the future together

The Sustainable Smart City Partner Program is a framework through which practitioners move forward together, guided not by hierarchy but by shared purpose. Across regions, SSPP serves as a conduit for learning and collaborative problem-solving. Its strength lies in asking sharper questions, implementing insights and reimagining vacancy as possibility — turning passive spaces into active invitations for change. Communities don’t predict futures; they build them.