There’s something freeing about ending the workday and shutting off that professional part of your brain — or so we’ve heard. It’s not exactly our experience at The Narwhal, but many of us also wouldn’t have it any other way.

When your job involves reading, writing and sharing stories of the natural world, you can’t help but find glimpses of it all around you: whether in interacting with nature — The Narwhal team loves a good walk (and more rugged adventures that we won’t get into here, but do in our members newsletter) — or reading about it.

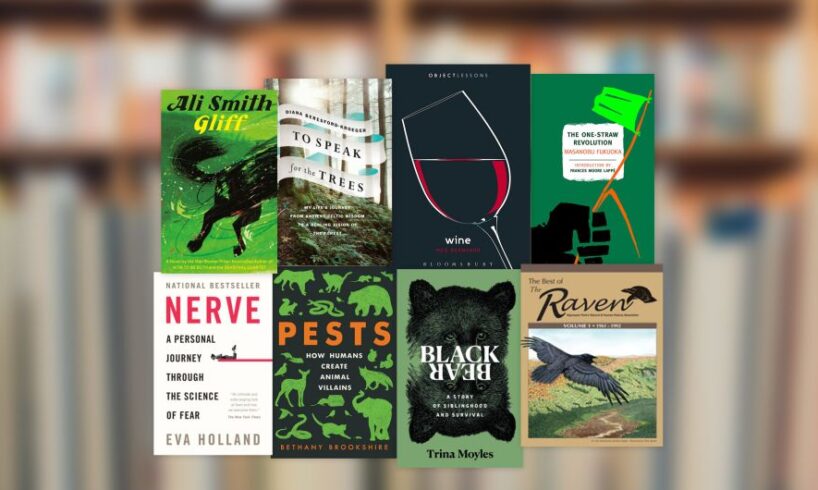

Over a year of ups and downs in really every way possible, many of us found comfort and entertainment in books and, at times, gravitated toward titles that touch on the topics we cover at The Narwhal.

From toiling in vineyards to unearthing ancient Celtic wisdom on the natural world, these stories captivated us, and were a reminder of why we are so lucky to do what we do.

From our bookshelves to yours, here are a few books we read in 2025.

Wine

By Meg Bernhard

American indie press Bloomsbury bills its Object Lessons series as “a book series about the hidden lives of ordinary things.” In her entry on one of humanity’s most beloved libations, journalist Meg Bernhard pens a beautiful, personal meditation on wine and the complex cultural, social and environmental issues underpinning her favourite drink. Framed through her experiences being introduced to wine in her 20s and then working on vineyards in Spain, where she came to appreciate wine as both an agricultural product and an art form, Bernhard offers a fresh and surprisingly moving account of a centuries-old beverage. Weaving seamlessly between the intimate — detailing her family’s relationship to alcohol and the women winemakers who helped develop her palate — and systemic — exploring sexism in the wine industry, migrant agricultural work and the effects of climate change — Bernhard manages to combine memoir, travel writing and journalistic reportage to produce a book that is anything but a stuffy treatise on tasting notes and point scales (it may actually make you rethink the former). It’s the perfect gift for the wine lover in your life who cares about complicating the narrative and good writing.

-Paloma Pacheco, assistant editor

To Speak for the Trees

By Diana Beresford-Kroeger

Orphaned at a young age, Diana Beresford-Kroeger was raised by her bachelor uncle, whose vast library — and quiet evenings spent reading beside him — formed her school years in County Cork, Ireland. She spent summers with her great aunt and uncle in the Lisheens Valley, learning the language of trees and their fundamental role in our existence, even after so much of Ireland’s forests were logged by the Brits. To Speak for the Trees follows these summers working with her Celtic elders and the earth, gleaning an incredible depth of knowledge from both. It continues as she marries this understanding with academic scientific study to become a highly recognized author, botanist and biochemist, now based outside Ottawa, and a leader in climate change solutions; if each person planted a tree a year for the next six years, we could heal the Earth, she simply notes. She closes the book with the Ogham script, the alphabet of the old Irish language with each letter corresponding to a tree — their essential role in our lives intrinsically written. It’s a retelling of ancient wisdom for a new audience that desperately needs to hear it.

-Elaine Anselmi, bureau chief

Trina Moyles’ memoir Black Bear weaves together a personal story with the story of coexistence between humans and wildlife, writes managing editor Sharon J. Riley. Photo: Trina Moyles

Black Bear

By Trina Moyles

Through all of Yukon-based journalist Trina Moyles’ reporting (some of it for The Narwhal), her deep connection to both rural and remote areas and the people and animals that live in them shines through. Black Bear, in a way, explains the roots of that empathy. Moyles grew up in northwestern Alberta in Peace Country, where growing up as a young girl, bears were an ever-present part of reality. But they weren’t the only threat Moyles — and other young women — learned to live with. “Our coming of age in a resource town in northern Alberta would require different survival strategies,” she writes. “I would learn how to fawn and please, but also how to physically fend off an attack and defuse threats — not only from bears, but from boys and men.” Her memoir is a beautiful tangle of interconnected narratives. To learn to survive as a young woman in a “hard-drinking resource town,” Moyles signed up for a self-defence course — taught by a conservation officer with a black belt in karate who had worked for the government to set leg snares for bears. But Moyles doesn’t focus on childhood alone. The book is about “coexistence with bears in the boreal forest,” and a reflection on what she learned from her dad, a bear biologist, along the way. Come for the bears, but stay for the heart-wrenching and personal story.

-Sharon J. Riley, managing editor

The One-straw Revolution

By Masanobu Fukuoka

A microbiologist and plant pathologist, Masanobu Fukuoka (1913-2008) turned away from “modern” agriculture in 1937 and looked instead to nature, learning how to grow food by mimicking natural processes using a method he called shizen nōhō (自然農法) — “Do-Nothing” farming. His 1975 manifesto is a practical guide to farming techniques and principles that helped spur movements like permaculture and regenerative agriculture — and it’s also a philosophical treatise on aligning ourselves to the rhythms of the land. Interspersed between chapters on rice cultivation, how to help soil regenerate its microbiome and the perils of large-scale commercial farming, Fukuoka offers moments of commentary on why he believes a return to nature is necessary. “Human beings are the only animals who have to work,” he writes, “and I think this is the most ridiculous thing in the world.” Instead, he suggests by attuning ourselves to the land to harvest only what we need to live, we are “simply doing what needs to be done.”

-Matt Simmons, reporter

Shining a light in dark corners

The Narwhal’s reporters dig deep to uncover facts that politicians might prefer to keep hidden. We need to raise $300,000 this December to keep our investigative journalism going in 2026.

Will you join the 1,000 readers and counting who’ve already stepped up to give? Every dollar you donate will be matched!

Let’s make double the difference

Gliff

By Ali Smith

What begins with an homage to fairy tales — siblings named Briar and Rose are abandoned in a cottage by their mother and her boyfriend, and left to fend for themselves — evolves into a strange and lovely story about humanity and collective resistance. The title, Gliff, comes from a Scottish word for a fleeting glance or moment, and is also the name Rose gives to a horse she finds in a pasture behind the house. The siblings exist on the margins of a world like our own — everyone is absorbed in their phones and ruled by algorithms — but the sinister aspects of technological dependence and state surveillance have been cranked up a notch; by the end you’ll want to throw your phone in a lake. Ali Smith has an abiding and empathetic interest in outsiders, and an unparalleled facility for pleasurable wordplay; her sentences romp across vast green fields of meaning, offering an essential template for examining a troubled world clearly — and without losing hope.

-Michelle Cyca, bureau chief

Reporter Shannon Waters was fascinated — and charmed — by some of the world’s least popular animals, like pigeons, in author Bethany Brookshire’s book Pests: How Humans Create Animal Villains. Photo: Carlos Osorio / The Narwhal

Pests: How Humans Create Animal Villains

By Bethany Brookshire

Bethany Brookshire offers a thoughtful and engaging exploration of the relationships human beings have with the creatures that share our world, whether we want them to or not. What makes an animal a pest? Why are some venerated as wildlife and others pampered as pets? In most cases, those categorizations “aren’t about the animals themselves, they’re about us,” Brookshire writes. From pigeons to pachyderms — yes, some elephants are considered pests! — each chapter examines the histories, misconceptions and contradictions we hold about the animals we love to hate. You’ll learn at least as much about human nature and culture as you will about the critters we’ve branded as vermin for insisting on existing in the spaces we’ve claimed as our own.

-Shannon Waters, reporter

Nerve: A Personal Journey Through the Science of Fear

By Eva Holland

What does it look like to face your biggest fears? And why do our brains get so scared? These are some of the questions that Whitehorse-based journalist and writer Eva Holland answers through her book Nerve. Eva’s willingness to let you into her brain as she navigates her mother’s death and how it connects to her crippling fear of heights makes for an incredible read. As do her efforts to overcome that fear, including from the tops of mountains. Like any good journalist (and one who has written for The Narwhal before), Eva digs into the facts and presents the science behind fear, making a compelling case for why we need fear in our lives and how to navigate it.

-Lindsay Sample, bureau chief

The Best of The Raven

By Russ Rutter and Dan Strickland

While visiting Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario this year, I discovered a real gem of environmental science writing. The park’s newsletter, The Raven, has been published fairly regularly since 1960, and The Friends of Algonquin Park has produced anthologies of the newsletter’s best issues. I devoured these anthologies in 2025, drawn in by the accessible science writing, but also by the natural and cultural history captured by these archival newsletters. Read as a whole, they document a changing ecosystem, covering, for example, the collapse of Algonquin’s deer population in the mid-20th century. The newsletters also describe the shifting ways humans have engaged with nature in the park; I was intrigued to learn that before those deer disappeared, they would congregate on the shoulder of Highway 60 and eat from the hands of park visitors. These Raven anthologies are a great read for any lover of Algonquin Park. As for my next discovery, I was recently tipped off to the existence of The Crow, a parody of The Raven produced by park employees in the 1970s and available to view at the Algonquin archives!

-Will Pearson, assistant editor