A man who used an onboard emergency hammer to smash a hole in the window of a stalled train to relieve the suffering of his fellow passengers in a sweltering carriage has become an unlikely and memeworthy hero. His small act of rebellion—in defiance of a perspiring train attendant who half-heartedly attempted to stop him—has become a timely metaphor for other forms of altruistically motivated disobedience.

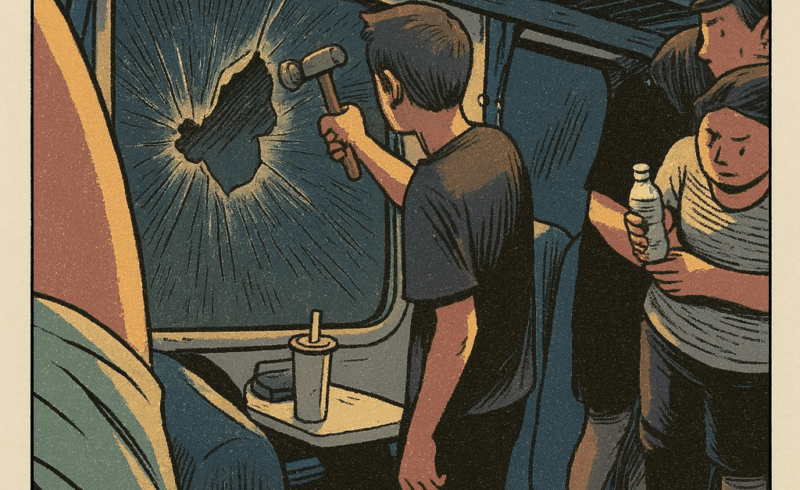

A screenshot from a video shows the moment that a young man in a black t-shirt smashes a hole in the window of a train carriage, while other passengers and a blue-uniformed train attendant look on. (source: NetEase News | Inspur News)

The incident occurred in Zhejiang province on the evening of July 2, after a freight train collided with a high-speed passenger train (K1373) en route from Shanghai to Huaihua in Hunan province. The collision derailed the passenger train and caused its ventilation and air-conditioning systems to fail. For nearly three hours, passengers were confined to the train carriages, where temperatures reportedly soared as high as 38°C (over 100 °F) and some passengers experienced symptoms of heatstroke. Video and photos of the scene show passengers and train attendants sweating profusely, with some of the male passengers having stripped off their shirts. In desperation, one of the passengers in carriage number three—a young man in a black t-shirt—used an onboard emergency hammer to smash a hole in one of the carriage windows. After the train resumed moving and arrived at a nearby station, the man was detained and scolded by railway police, who later issued a statement saying that the man’s decision to smash the window was unwarranted, as the situation did not meet the criteria of an “emergency.” (Eyewitness accounts and photos shared online, some since censored, appear to contradict the claim that the man overreacted.)

An illustrated comic-style meme of the window-smashing incident bears the caption, “Smash that window, and take a breath of freedom.” (source: WeChat)

In the comment section below railway officials’ statement on Weibo, initial reactions were mixed. Some commenters felt that the man had overreacted, while others insisted that his actions were justified because he had helped to avert heatstroke or heat sickness among his fellow passengers. Still others hailed him as a hero for having the courage to take action in a dangerous situation, even if it meant disobeying the orders of the train attendants or defying the railway police. The window-breaking incident became a hot topic online, inspiring articles that focused on a number of angles: the man’s courageous disobedience; the health dangers of extreme temperatures; railway accidents and railway officials’ disregard for the health and safety of the stranded passengers; and an official statement that seemed to sidestep responsibility for the inciting collision. (For an historical perspective on these issues, see CDT’s interview with historian Jeremy Brown on how the Party-state has handled past disasters and accidents.)

CDT Chinese editors have archived over a dozen related articles and essays, at least two of which have been deleted by platform censors, as well as a roundup of online comments and memes. One of the most widely shared quotes, from internet user 佛山孔兄 (Fóshān Kǒngxiōng, “Brother Kong from Foshan”), was “Smash that window, so we can all breathe some fresh air!” In his full post, Brother Kong made an explicit comparison to the devastating July 2021 floods in Zhengzhou, Henan province, during which over a dozen people died in a flooded subway station. (At the time, Zhengzhou subway management was accused of “homicidal negligence” by angry members of the public, and the topic has been heavily censored online ever since.) Another popular comment came from Weibo user 默言 (mòyán, “speechless”): “Let’s put it this way: if this had been a shipment of hogs, someone would have come to their rescue much sooner.” (While there are stringent government guidelines for regulating the temperature in freight trains transporting livestock such as hogs, the standards for passenger trains seem to be left to the discretion of railway personnel.)

A slogan on the wall of a train station reads, “Service is our mission: we treat travelers like family.” (source: WeChat/大何崛起)

A strongly worded essay from WeChat account “Da He Rises” (大何崛起, Dà Hé Juéqǐ), dissects the official statement from local railway authorities and lambasts its self-congratulatory tone and elision of some key details. For example, while the statement trumpeted the fact that that 10 ambulances were readied in case of injury or illness, and that railway staff were dispatched to hand out bottled water and canned congee to the stranded passengers, it neither apologized nor accepted responsibility for the collision between the freight and passenger trains, made no mention of the number of passengers on the train, and claimed that temperatures inside the carriages never exceeded 31°C (88°F), far below passengers’ estimates of 37-38°C (98.6-100.4°F). A portion of Da He’s essay is translated below:

This kind of condescending arrogance leaves me speechless.

[…] Upon reading the entire statement, you will notice something strange.

While it was clearly the railway system’s own scheduling snafu that caused the accident, this was glossed over in the statement.

Instead, the focus was on the window-smashing passenger, who it says was “lectured and reprimanded.”

The statement reads like a self-commendation, bragging at length about their own hard work and noble intentions, and tossing in details such as how they managed to distribute 40 bottles of water to the passengers.

The only thing they left out were the two most important words: “We apologize.”

The gist of the statement seems to be this: “It wasn’t our fault, and everything we did was for your own good. As for that window-smasher, we are inclined to be magnanimous and let him off with a lecture and a reprimand.”

So I found it hilarious that the statement concluded by calling on the public to always heed the orders of railway personnel in the event of an emergency.

Here’s the simple truth, my friends, and it may save your life:

In emergency situations, protecting human life should be the priority. To this end, everyone should have the right to ignore the rules if it allows them to stay out of danger and protect themselves. [Chinese]

Some online commentators mentioned the dangers of extreme heat, discussing recent climate-change-induced heat waves, and comparing the train incident, in which all of the passengers survived, to the recent heat-related death of a dormitory guard at Qingdao University in Shandong province. Zhang Peisheng, a man in his late 50s, died of heatstroke in his tiny, poorly ventilated, non-air-conditioned bungalow/office next to the dormitory. A statement issued by the university on July 6 was widely criticized for omitting the man’s name and actual cause of death, and generally failing to take any responsibility for the conditions that likely led to his demise. During this period, the news was filled with stories of students from Qingdao and other cities in Shandong being hospitalized with heatstroke, or trying to escape their sweltering dorms by loitering in air-conditioned supermarkets. One viral image “showed a thermometer reading 43.2°C (nearly 110°F), taken inside the office of the guard who had died.”

CDT Chinese editors have archived a number of articles about Zhang’s death and the university’s attempts to deny culpability. A WeChat article by current-affairs commentator Wei Chunliang characterized the statement from Qingdao University as “cold-blooded,” noting that it was released in the middle of the night when it would not attract too much attention, neglected to include Zhang’s name, was vaguely worded, and avoided any mention of heatstroke as a cause of death. Another WeChat article, from the account Unyielding Bamboo, pointed out a common thread in official statements released by railway authorities after the K1373 derailment, by Qingdao University after Zhang Peisheng’s death, and by local authorities after a mass lead-poisoning incident at a kindergarten in Tianshui, Gansu province. All of these statements elided or misrepresented the facts, and none made any attempt to apologize or accept responsibility for the incidents. “When their first response is to lie and deny,” wrote the author of the article, “when they pay no price for such behavior and are given latitude to behave the same way in the future, then the same problems are certain to recur.”

A WeChat article by Bao Renjun, titled “The Passengers Who Didn’t Die From the Heat, and the Old Man Who Did,” takes aim at some of the online comments that criticized the K1373 window-breaker for defying the instructions of the train conductor, despite the fact that the young man’s action may well have prevented heatstroke among his fellow passengers. Comparing that incident with dormitory guard Zhang’s death, Bao Renjun writes:

On the surface, both of these incidents are related to the hot weather, and have the same underlying cause. When will we finally begin treating people as human beings?

“Human life above all” should be more than a mere slogan. In a life-or-death situation, even a single life—to say nothing of an entire train filled with people—should outweigh [any potential damage to] a train carriage. [Chinese]

Quite a few of the archived articles focused on the topics of courage and disobedience. In a short piece on his WeChat Moments, a portion of which is translated below, journalist Zhang Feng shared some thoughts on habits of obedience instilled during three years of “zero-COVID” lockdowns, and how “the courage to smash windows requires practice:”

This incident sparked widespread discussion, and caused many to wonder: as the temperature in the carriage soared to 31 degrees, and everyone was dripping with sweat, and some passengers were experiencing chest pains or difficulty breathing, why did so many remain docile?

In such a culture of obedience, was the man who smashed the window an aberration?

Accusing “everyone” of being overly docile simply reflects our general sense of anxiety, because of course “we” are included in that catch-all “everyone.” And so we must examine our consciences and ask, “What would I have done in that situation?”

It hasn’t been long since the three-year pandemic ended, and many of us look back on our docility during that period with shame. But have we truly stopped to question it? This train incident presents us with a new test. [Chinese]

A WeChat article from commentator Xiang Dongliang praises the train passenger’s courage, and imagines what thoughts might have filled the young man’s mind as he decided to risk punishment by breaking the window:

As Chinese people, we can certainly imagine the inner struggle he went through before smashing the window:

“If I swing this hammer, will I be arrested? How much will they fine me? Will it leave me with a criminal record that might someday disqualify my kids from taking the civil-service exam?”

These are completely plausible consequences in China, and they are the most immediate explanation for why he alone, among an entire trainful of people, dared to smash the window.

For so many millennia have the Chinese people been docile …

If I’d been on that train, it definitely would have occurred to me to break a window to get some fresh air, but I’m not sure I would have had the courage to actually swing that little hammer. [Chinese]

Journalist Song Zhibiao, who frequently writes about social issues, discussed the K1373 incident as a metaphor for society, and concluded that “disobedience may be our only avenue of escape”:

In many films, from “Murder on the Orient Express” to “Snowpiercer,” the enclosed nature of a speeding train is imbued with profound metaphorical significance. One young man’s act of smashing a window on the K1373 train transformed what might have been an ordinary “accident” into an occasion of great symbolic import. Raising a hammer to that window signalled rebellion against an inept railway rescue, an act of disobedience that opened an avenue of escape for everyone.

In this case, “everyone” includes the young man who broke the window to let in some fresh air, as well as hundreds of other passengers, the railway police and attendants who failed to communicate with the railway authorities, and still others who were not on the train but would certainly have been affected if a secondary crisis had occurred. The young man broke not just a window, but also a deadlock that might well have ended in disaster.

[…] Thanks to one brave young man’s disobedience, the other passengers were given the chance to breathe—or, we might even say, a chance to live. It was a meaningful moment, for while the young man’s disobedient window-smashing may have escalated the situation, it also greatly reduced the risks of that situation. Disobedience is not a provocation, but a liberation. [Chinese]

Lastly, a WeChat article by Beijing-based attorney Hu Changpeng compares K1373’s altruistically disobedient passenger to other “openers of windows,” such as lawyers who stand up for their clients’ rights in court and challenge unjust or unreasonable rules. Hu encourages readers to value these individuals for their contributions to Chinese society as a whole, and for their commitment to giving everyone “room to breathe”:

Those who dare to strike back at unreasonable rules are an important force for societal self-renewal. To cherish them is to cherish everyone’s right to breathe freely. For when the last window is sealed shut, we lose not only our supply of oxygen, but also our courage and capacity to change the status quo. [Chinese]