1.

The question of applying Israeli sovereignty across the entire Land of Israel has reemerged. As I write, calls to support it in a Knesset vote are being heard. Let it be so. It’s no coincidence that this week the Knesset hosted a conference organized by the Sovereignty Movement, in the same week that the Torah reading includes the ancient biblical command to establish sovereignty over the land. Circles open and close; we, an eternal people, illuminate the present through the formative stories we have read for thousands of years, stories that became core elements of our national identity.

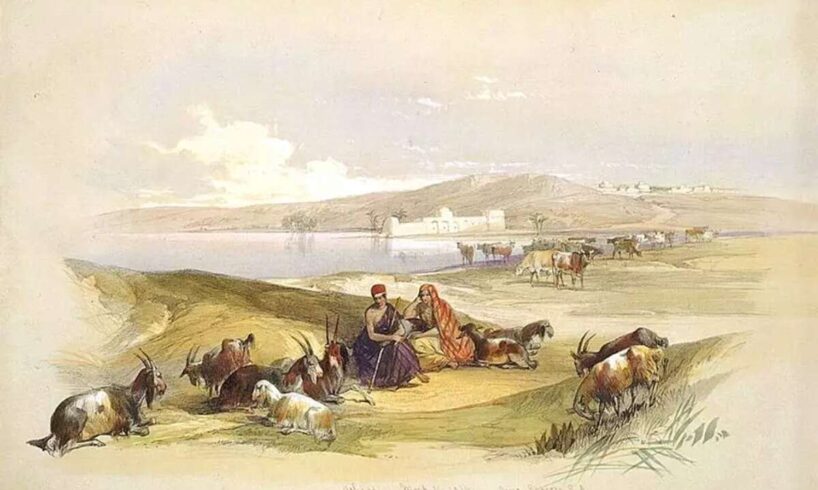

This Shabbat we conclude the Book of Numbers. Our people have always journeyed from Egypt to Jerusalem, whether through the Sinai wilderness or the wilderness of nations, for 40 years or 2,000. In our collective memory is the promise of returning home to Zion. Jews have lived in the land even during the long exile under foreign rule.

2.

The final portions of Numbers take place in the 40th year of the Israelites’ wandering. The people are encamped in the plains of Moab, east of the Jordan River, opposite Jericho. Within months, they will bid farewell to Moses and cross the Jordan led by Joshua, to conquer and settle the land. In the meantime, Moses speaks, teaches and advises, like a father giving final instructions to his children before death. From this point through the end of the Torah, he repeats a pair of terms essential to our future in the cherished land of our ancestors. The first time appears in this week’s Torah portion:

“For you are crossing the Jordan to come to the land of Canaan… and you shall Take possession of the land and dwell in it, for I have given you the land to possess it. And you shall inherit the land…” (Numbers 33:51–53).

To settle and dwell in the land means to build homes, raise families, plant trees, make the desert bloom, and pave roads. But all of this can also be done under foreign rule. In 1492, Shlomo Caro was expelled from Spain at the age of four. At 48, he immigrated to Safed, where he wrote his revolutionary legal code, the Shulchan Aruch. His colleague, Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz, also settled in Safed and wrote the famous hymn “Lecha Dodi,” calling upon Jerusalem: “Royal sanctuary, city of sovereignty, rise up from your ruins! Too long have you dwelled in the valley of tears, and He will have mercy upon you with compassion.”

At the time, the Ottomans ruled the land. Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent was renovating the walls of Jerusalem. They lived in the land, but under foreign control.

3.

This is why Moses doesn’t stop at commanding the people to dwell in the land. He adds: “You shall take possession of the land,” and later in Deuteronomy: “Go in and possess the land,” “You shall come and possess the land,” and so on. Individuals may inherit private property, but not an entire country. For that, a nation must arise and establish a political and sovereign entity that will apply the people’s sovereignty to the land. Only then can it be passed on to future generations. This was how Rabbi Moses ben Nachman (the Ramban, known as Nachmanides) understood it when he arrived in the land in 1267.

After publicly defeating the convert Pablo (Saul) Christiani in a debate in Barcelona, Nachmanides fled Girona. The Catholic Church was unhappy with his victory and pursued the great sage to force him to recant. He reached Acre and continued south to Jerusalem, where he tore his garments in mourning over the city’s devastation. To his son in Spain, he wrote:

“The desolation is great and the ruin immense… Jerusalem is more devastated than all, and the land of Judah more than the Galilee… There are no Jews in it, only two dyer brothers… and they gather a minyan [quorum for prayer] in their home on Shabbat.” And so, he renewed the Jewish presence in the city.

Nachmanides interpreted Moses’ words not as a declaration, but as a perpetual commandment, even during exile: “He commanded them to dwell in the land and to possess it, because He gave it to them, and they must not despise the inheritance of the Lord.”

In his additions to Maimonides’ Book of Commandments, he wrote: “We are commanded to inherit the land which the Almighty, may He be blessed and exalted, gave to our forefathers – to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob – and not to leave it in the hands of other nations or abandon it to desolation.”

Not leaving it desolate, meaning to settle and develop it, but the primary directive is not to leave it under foreign control, but to possess it. In modern terms: to apply national sovereignty, to establish a state. The difference is like that between a platonic or causal relationship and formalized marriage, which reflects the seriousness and strength of the bond.

4.

Almost as a side note, Nachmanides included a key phrase: by settling the land and inheriting it, the people will show that they “do not despise the Lord’s inheritance.”

The root cause of exile and destruction was the sin of the spies, who preferred to remain in the wilderness, symbolizing the preference for exile over life in an independent state. In place of the generation of slaves who left Egypt, a generation of Canaanite conquerors would arise:

“I will bring them in to enjoy the land you have rejected” (Numbers 14:31).

The Psalmist describes it this way: “They despised the pleasant land, they did not believe His promise. They grumbled in their tents and did not listen to the voice of the Lord. So He raised His hand to overthrow them in the wilderness, to overthrow their descendants among the nations and to scatter them throughout the lands” (Psalms 106:24–27).

Thus, we see the link between rejecting the land and the exile we mourn on Tisha B’Av.

Inheriting the land, applying sovereignty, is the rectification of that historical disgrace, and a declaration to the world: the Jewish people have returned home and are settling across the land, and not only settling it but also asserting sovereignty over it.

Caleb son of Jephunneh stood against the spies who slandered the land and proclaimed: “We shall surely go up and take possession of it, for we can surely overcome it!” (Numbers 13:30).

The antidote to the sin of the spies is thus to return to Caleb’s original plan: to inherit the land.

5.

In the 1880s, Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (the Natziv) published his Torah commentary Ha’amek Davar. This was a time of renewed settlement efforts in the Land of Israel by the Lovers of Zion movement, in which the Natziv was active.

Interpreting the verse, he wondered why the sequence is to first dispossess and then dwell in the land. Shouldn’t it be the other way around, first settle and then inherit?

He concluded that settlement must be for the purpose of acquisition, not mere dwelling, but dwelling with the intent to inherit: “If they settle not for the sake of inheritance, they have acquired nothing.”

If settlement is “private” – individuals fulfilling the commandment to dwell in the land and nothing more – it will not suffice to make the land a national possession. Hence, the verse’s sequence is correct: inheritance comes through dwelling, but only when done with the national intent to possess the land.

In other words, the highest level of settlement is one that aims to inherit the land, based on a national vision, with the ultimate goal of applying the people’s sovereignty over their land.

6.

Nachmanides wandered through a desolate land, but he saw far into the future and believed that all the prophets’ promises would be fulfilled. That is how he justified his dangerous journey in old age from Spain to the Land of Israel:

“…And this is what drove me from my land and displaced me from my place; I left my home, I abandoned my inheritance, I became like a raven to my sons, cruel to my daughters, for I desired that the upheaval of my soul would end in the embrace of my mother.”

That mother is the Land of Israel. His deepest yearning was to place his soul, after long exile and wandering, in the arms of his true mother, the land of Israel.

When the nation arrives en masse to do the same, the land will bloom, until the world will say:

“This land that was laid waste has become like the garden of Eden; the cities that were lying in ruins, desolate and destroyed, are now fortified and inhabited” (Ezekiel 36:35).

And we have seen it with our own eyes.

The post 'I want to be the displacement of my soul, in my mother's embrace' appeared first on www.israelhayom.com.