Gary Goode served as an infantry soldier at CFB Gagetown in New Brunswick for almost three and a half years in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. Decades later, Goode was diagnosed with lung cancer and, in 2005, he had his right lung removed. Goode said his thoracic surgeon explained his symptoms were aligned with exposure to Agent Orange — the infamous herbicide mixture used by the American army during the Vietnam War to destroy food crops and reduce hiding spots in the dense jungle.

Agent Orange and other herbicides were tested at Gagetown in 1966 and ‘67. During his recovery, Goode began to research the chemicals used at the base where he served. Goode said he was never told about the risks of these chemicals, which he never saw being sprayed — he believes it happened shortly before he began his service.

“We could tell because everything was dead brown or yellow,” Goode told The Narwhal about the base. “We were drinking the water that was in the area [and] the dust would be sticking to us. … There was a lot of dust.”

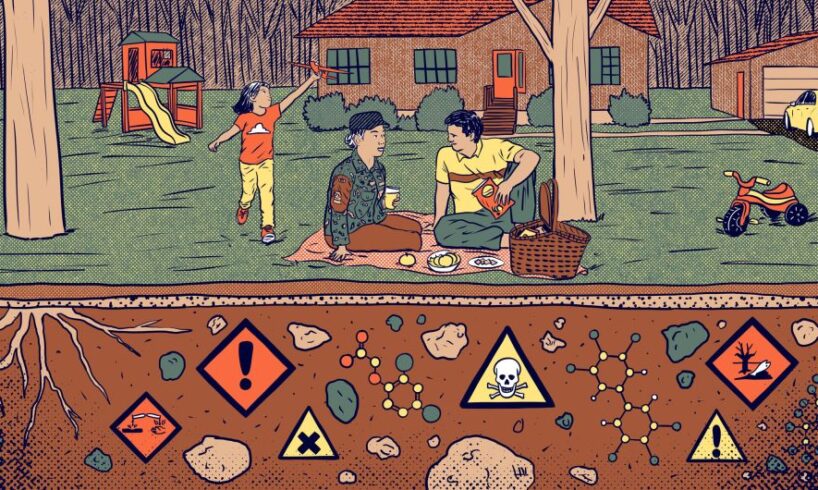

Now, Gagetown is one of the sites where Canada’s Department of National Defence plans to build new housing for military families, even though the base is listed on the federal government’s inventory of contaminated properties. These are sites where known chemicals in the water and soil include per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS, often referred to as “forever chemicals”), petroleum hydrocarbons and, at Gagetown, Agent Orange — contaminants that carry exposure risks including cancers, heart issues and immune dysfunction.

Sites owned by Canada’s Department of National Defence that are known (red diamonds) and suspected (yellow diamonds) to be contaminated. Source: Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory. Map: Nikita Wallia / The Narwhal

National Defence doesn’t deny the use of Agent Orange at CFB Gagetown. In 2007, Canada allotted $95.6 million toward compensating military members and civilians who may have been exposed to it from working at or living near the base when it was sprayed. Goode and more than 5,000 others have received $20,000 payments, even as the government maintained Agent Orange exposure didn’t mean an “increased risk for long-term, irreversible health effects.” It called these payments “ex gratia,” or made out of a moral imperative rather than a legal one.

Goode is now chairman of Brats In The Battlefield, a group of veterans whose social club morphed into advocacy as the extent of the contamination issue at Gagetown became clear. The group still wants an independent investigation into the contamination. It questions the rigour of the government’s studies and assessments and says the scope of the problem and the long-lasting impacts have still not been properly understood.

The housing plan announced last January further convinced Goode that National Defence still isn’t taking the lingering effects of decades-old contamination seriously — not just at Gagetown, but on other sites the department owns that are among the thousands of listings in the massive public database of contaminated federal sites.

The military says it’s building 668 new housing units on bases across the country to help solve housing shortages for Armed Forces members and their families. Construction is supposed to take place over the next five years.

The pressure to house military families will only grow: Prime Minister Mark Carney has pledged to more than double military spending by 2035 and National Defence has committed to “rebuilding” to 71,500 regular force and 30,000 reserve force members before 2032. Photo: Chris Young / The Canadian Press

Along with Gagetown, units are planned in Halifax, Edmonton, Esquimalt, B.C., Valcartier, Que., as well as in the Ontario communities of Trenton, Borden, Kingston and Petawawa. All of these bases already have housing and all are on the contaminated sites list: in a press release, the department said locations were chosen in part based on high numbers of new members. Some contamination has been remediated on several of them, including Trenton and Borden, but much has not been fully addressed.

Soon, there might be more military families looking for homes. Recruitment is set to increase — Prime Minister Mark Carney recently said Canada will more than double current military spending, in line with a pledge with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO, to invest five per cent of annual gross domestic product on military spending by 2035.

With National Defence committing to “rebuilding the military” to 71,500 regular force and 30,000 reserve force members before 2032 to help Canada address shifting security needs, the pressure to develop housing quickly will only grow. But advocates like Goode are hoping that housing won’t be just fast — but that it will also be safe for the military families who will call it home.

A long list of contaminants are present on federal sites across Canada

National Defence says it urgently needs more people. It also urgently needs more housing. A 2023 report said members of the Armed Forces and their families feel the impacts of the national housing crisis even more acutely than the average Canadian because many of their jobs require constant relocation. At the same time, CBC has reported, the military is short more than 13,600 members: in February, its surgeon general said the Forces will now consider applicants with “any and all conditions” for enrolment, including asthma.

But fixing one problem shouldn’t cause another, according to former NDP member of parliament Lindsay Mathyssen. “It’s important that we’re obviously investing in housing, but safe housing where we don’t have to worry about those things. There’s a whole slew of issues here, both past, present and now, future, that have to be dealt with,” Mathyssen told The Narwhal in January 2025, before she lost her seat in the April election.

After her attention was drawn to a site in her Ontario riding, Mathyssen initiated a National Defence standing committee study of contaminated sites last winter. Goode and other veterans testified at the four meetings, including staff from CFB Moose Jaw in Saskatchewan, where many believe their illnesses are connected to on-site contamination.

Mathyssen told The Narwhal any housing plans for contaminated bases must ensure safety. “We’re asking so much of people; they put their faith, their trust, in their institutions and government and they defend them, sometimes with their lives,” Mathyssen said. “We can’t take that for granted.”

Typically, air, water and soil contamination is up to provinces to monitor, halt and remediate. But federal departments carry that responsibility for their properties. The National Defence website says it manages contaminated sites “by prioritizing sites based on human health and environmental risks.”

For example, both Environment and Climate Change Canada and Health Canada told The Narwhal they have not studied the areas on or surrounding the Gagetown base for contaminants and their impacts, as it’s the responsibility of National Defence. New Brunswick’s Department of Health told The Narwhal provincial departments “only become involved when made aware of significant concerns regarding potential contamination that may pose a risk to human health in areas beyond, but excluding, the base itself,” which it said isn’t the case with CFB Gagetown.

An armoury in Moose Jaw, Sask. The National Defence website says it manages contamination “by prioritizing sites based on human health and environmental risks.” Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Some of the contaminants on federal sites have made headlines, particularly PFAS, which are found on more than 100 of them across Canada, often due to foam used to train firefighters for decades. Of the proposed military housing sites, Trenton, Gagetown and Edmonton are listed as sites of the chemicals according to the federal inventory. The United States Environmental Protection Agency lists potential health risks of PFAS exposure including reproductive problems, developmental effects in children, increased risk of certain cancers and weakening of the immune system. The Canadian government says PFAS can be transferred through the placenta during pregnancy and through ingestion of human milk.

Several of the sites, including Petawawa in Ontario and Esquimalt in B.C., are further contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyls, a group of synthetic chemicals known as PCBs. Once widely used for things like coolant in electrical appliances, PCBs have been illegal to release to the environment in Canada since 1985 because they can have persistent and hazardous impacts on health and the environment. The United Nations Environment Programme has reported that both PCBs and PFAS can accumulate in the tissues of plants and animals, becoming more concentrated and harmful as they move up the food chain.

Other entries on the long list of contaminants at Trenton include a group of petroleum hydrocarbons known as BTEXs — benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene. BTEXs have numerous health impacts associated with inhaling them, accidentally ingesting them or making skin contact. According to a peer-reviewed study from the Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, these include increased risk of respiratory and lung cancers, heart problems and heart failure, blood disorders, immune dysfunction and increased susceptibility to infections.

An air traffic control tower at CFB Moose Jaw in Saskatchewan. Retired aircraft technician George Westcott worked and lived at CFB Trenton in Ontario for decades, and said his late wife is one of a number of people whose cancer deaths he believes are linked to contamination on base. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Former staff at CFB Trenton told The Narwhal it’s generally understood these sites are contaminated, even if the specific chemicals or effects aren’t common knowledge. Among them was retired aircraft technician George Westcott.

“You wouldn’t believe how many people that we worked with died while we were working there … from cancer,” Westcott said. He worked and lived on CFB Trenton for decades over his career, often working with jet fuel and other harmful solvents. “My wife included.”

Westcott lived in on-base quarters with his wife, Pamela, who passed away in 2023 from a type of lung cancer called mesothelioma that quickly metastasized to her brain and bones. Being around asbestos — which is known to be present in non-residential buildings at CFB Trenton — is the biggest risk for this type of cancer. Westcott told The Narwhal he is concerned the contamination will continue to harm new families who live there, like he believes it harmed his.

“I’m not asking for anything, but I would ask for it to get recognized for the next poor people so that it doesn’t happen to somebody again,” Westcott said. “God help the people that are going to be living there.”

National Defence told The Narwhal that Privacy Act limitations mean it is “not able to discuss the medical conditions of current or former members, nor the alleged causes.”

Some military sites have been cleaned up — but it’s expensive and time consuming

Contamination cleanup is underway on some military sites, but it takes time and money. In 2024-25 alone, National Defence received $66.6 million to reduce legacy contamination at sites including Esquimalt’s harbour, through a nationwide fund dedicated to dealing with the government’s contaminated properties problem.

In December, an assistant deputy minister in the department said National Defence had spent nearly $273 million managing contaminated sites over four years. In that time, more than 250 sites had been closed, meaning remediated or risk-managed enough to come off the list. The department also said it was on track to spend another $65 million to close another 50 sites this year.

CFB Borden is closed, according to National Defence, which told The Narwhal in an email that all necessary remediation work needed to construct the new barracks at the base was completed in 2021, at a cost of approximately $3.5 million. A bigger project to remediate PFAS-contaminated firefighting training areas, which entailed excavating and treating contaminated soil, cost another $16 million and was “substantially completed” by late 2022, the department said.

“We recognize the importance of being a good environmental steward and doing our part to address the effects of our operational legacy and safeguard the health of Canadians,” the department said in an email. It “employs a risk-based approach” to managing contaminated sites and generally does not tell employees or the local community what that approach is “until qualified environmental experts identify potential exposure risks.” It has had a 10-step approach in place since 1999 to identify potential hazards.

The department said that 16 years of ongoing cleanup at Trenton has included groundwater remediation and that it is assessing the effects of what’s been done before deciding on next steps.

The department told The Narwhal that remediation at Gagetown, which its website says is focused on petroleum hydrocarbons, not herbicides or other contaminants, is in progress. The department also said it is “not planning any further activities at this time” at Gagetown.

Cadet barracks at CFB Valcartier in 2015. In 2020, a Quebec court awarded millions of dollars to current and former soldiers and military families who drank water at the base tainted with a cancer-causing chemical called trichloroethylene, which leached into the water table for decades. Photo: Jacques Boissinot / The Canadian Press

In Quebec, the department has deemed the Valcartier site safe enough for housing. In 2020, the Quebec Court of Appeal awarded millions of dollars to current and former soldiers and military families who drank water tainted with cancer-causing industrial degreaser, used to clean metal equipment. The chemical, called trichloroethylene, leached into the water table when it was used at Valcartier’s research facility and a nearby ammunition factory from the 1950s to 1990s.

National Defence told The Narwhal it has implemented measures to ensure water on-site is safe to drink and that the trichloroethylene plume on the base is closely monitored, adding: “Importantly, the wells used for drinking water are located outside the boundaries of this plume, and testing confirms that the water drawn from them is not contaminated.”

It’s unclear what the next steps are for other proposed housing sites. The department said the Canadian Forces Housing Agency does not have a budget specifically for remediating sites proposed for new housing. It said it selects sites that either “have no known contamination,” or have “the potential to be remediated with reasonable costs.”

Cleaning up toxic sites for housing is a ‘win-win,’ expert says: ‘The issue is money to do it’

Toronto Metropolitan University professor Christopher De Sousa has studied redevelopment of what are known as “brownfields” — abandoned or unused industrial land that may be polluted — for both private and public projects. He told The Narwhal it’s possible for the Department of National Defence to redevelop contaminated military bases into safe places to live, with enough investment.

“The use of these kinds of contaminated properties for housing, there’s decades worth of experience in doing that kind of work,” De Sousa said, adding it is “nice to see” National Defence trying to contend with contamination and adding underused federally owned land to the housing stock. “Take your worst site that you could think of; if you want to turn it into housing, you can. … The issue is money to do it.”

De Sousa pointed to the example of the Port Lands in Toronto, once one of the largest wetlands on Lake Ontario, where both water and soil became polluted with spills from industrial and commercial uses including petroleum refining and hydrocarbon products manufacturing, alongside effluent from sewers and sewage treatment plants.

Construction work next to the waterfront in Toronto’s Port Lands, part of a long-term, $1.5-billion project to clean up the area where the Don River meets Lake Ontario. Photo: Christopher Katsarov Luna / The Narwhal / The Local

In 2017, all three levels of government made an initial investment of nearly $1.5 billion to begin to remediate the 356-hectare site. Eight years later, work is still ongoing — but in mid-July, part of it finally opened to the public, 20 hectares of a new park named Biidaasige, an Anishinaabemowin word meaning “sunlight shining towards us.”

“There’s been more pressure for these sites to be assessed, remediated and converted into something that adds more public value,” De Sousa said. “You want to get that win-win where you’re not just cleaning a site for the sake of cleaning it, you’re getting a public benefit. … But you need to be secure that those contaminants have been cleaned up.”

It’s not cheap or easy. More than two million cubic metres of contaminated soil had to be dug up and moved to a “containment area,” treated to remove contaminants and then reintroduced for future landscaping. Two years ago, the Toronto Star reported the Port Lands project was $169 million over budget. And, it’s taken a while: the design was chosen back in 2007, but construction is behind schedule. With progress finally visible, the goal is that, along with a cleanup and added parkland, the revitalized wetlands will help with the Don River’s tendency to flood.

The $16-million PFAS cleanup at CFB Borden was smaller, but still complex. Between 2020 and 2022, the process included excavating 91,000 cubic metres of contaminated soil from the base’s firefighting training area and disposing of it in an on-site containment cell: “The soil is wrapped up and contained, like a burrito, so it can’t leach into the ground,” a team leader with the Crown corporation Defence Construction Canada said in a press release as the project neared completion.

The limits of National Defence’s Agent Orange compensation in New Brunswick

One of the frustrations for those dissatisfied with National Defence’s response to contamination at Gagetown is the department’s limits to who it considers at risk.

Its terms for the one-time payment issued to Goode and others had strict requirements: individuals must have an illness associated with exposure to Agent Orange as determined by the U.S. National Academy of Medicine and must have worked at, trained at or lived within five kilometres of CFB Gagetown on the dates when Agent Orange was tested in 1966 and 1967. This limited compensation for members of groups like Military Widows on a Warpath, which claimed families were unfairly denied compensation because their service members died of contamination-related illnesses prior to the 2007 announcement.

Goode calls the proposed housing development in Gagetown “scary.” Apart from lung cancer like he had, Agent Orange is known to cause leukemia and bladder cancer, along with birth defects and Parkinson’s disease, according to the Cleveland Clinic. At least one toxin in Agent Orange can persist in the soil for up to 50 years, according to a study from the University of Illinois.

“We just don’t want this to happen again. That’s all we’re looking for,” Goode said. “We’re looking for truth, honesty, accountability and justice. … We want people to be compensated for their exposure to these chemicals at Gagetown and the diseases that have been debilitating them.”

National Defence is planning to build new housing at CFB Gagetown in New Brunswick, where Agent Orange was used in the 1960s and toxins including PFAS and hydrocarbons are known to be in the water and soil. Photo: Lars Hagberg / The Canadian Press

In 2019, as Brats In The Battlefield continued to push for an independent public inquiry at the House of Commons, the department reiterated human health risk assessments conducted in 2005 “concluded that most people who lived and worked at or near CFB Gagetown were not at risk of exposure to herbicides,” including Agent Orange. The same assessments found potential long-term health risks were “identified as a possibility for only those individuals directly involved with the application of the herbicides or clearing of treated brush soon after herbicide application.”

Meg Sears is chair of the organization Prevent Cancer Now, whose board is composed of physicians, environmental advocates and at least one veteran. She has been working to help Gagetown veterans and their families receive accurate data for decades. She calls the findings of the government study of Gagetown done between 2005 and 2007 “flimsy” — an opinion backed up last year by a commission in Maine, which looked into the health of National Guard members that had trained at the New Brunswick base and called Canada’s data “incorrect” and “biased.”

In its 2024 report, the Maine commission also criticized National Defence for taking its reports from the fact-finding mission offline, saying data being inaccessible to the public “undermines their scientific credibility and usability” (the reports are still available on the Prevent Cancer Now website). That same year, a spokesperson for National Defence told CBC the government has no plans to conduct further studies at Gagetown to look into the health impacts of past herbicide use.

“I find that it’s difficult to get data, and when you do get it, you’re usually missing some important part of the data to really get a good picture of what’s happening,” Sears said. She doesn’t feel great about the plan to build housing on Gagetown and other known contaminated sites.

“I don’t have a lot of confidence that the people who are going to be living on these bases are necessarily going to be as safe as they deserve to be in terms of their air quality and their drinking water quality,” Sears said.

“If CFB Gagetown is an indicator of how the Canadian Forces work in terms of protecting the people who step forward to look after us, I think that there’s an awful lot of room for improvement.”