Shafaq News

Welcome to Najaf — not your typical vacation brochure kind

of place. There’s no beach, no breeze, and frankly, not much shade. But what it

lacks in palm trees, it more than makes up for in spiritual weight and timeless

atmosphere.

Najaf perches on a desert plateau in southern Iraq, a

stone’s throw west of the Euphrates River. It borders Karbala to the north and

opens westward into the Arabian Desert. The landscape? Think cracked soil,

burning skies, and winds that whip sand into your teeth.

In the summer, Najaf doesn’t just get hot — it competes with

ovens. Temperatures frequently climb above 50°C, with 2024 alone seeing over 40

days of blistering heat above 48°C. Dust storms are regular guests,

occasionally hitting 70 km/h. And if you’re wondering about rain… well, let’s

just say umbrellas don’t sell well here.

Lake Najaf, once a vital water body, is now a memory in

retreat — it has shrunk by over 60% since the 1990s, thanks to overuse and a

climate that seems to conspire against farmers.

But the land tells another story, too. Najaf is sacred

ground.

Wadi al-Salam, the “Valley of Peace,” is the world’s largest

cemetery, with over 1,485 acres of tombstones, stretching to the horizon. It

houses more than five million graves. Why here? Because Imam Ali bin Abi Taleb,

the cousin of the Prophet Muhammad and the first Imam in Shiite Islam, is

buried nearby. And for millions, resting near him is the holiest of honors.

Yet the cemetery holds more than just recent memory. Wadi

al-Salam is also believed to cradle the graves of ancient prophets, including

Prophet Hud and Prophet Saleh, figures who appear in both Islamic and biblical

traditions.

By the Abbasid period, Najaf had already carved its place as

a bastion of Shiite learning. During Ottoman rule, the city preserved its

autonomy even while Baghdad danced to imperial tunes. In 1920, Najaf’s scholars

and tribes shook the British Empire with a revolt led by Ayatollah Muhammad

Taqi al-Shirazi. This was not just a city of prayer; it was a city of protest.

The 20th century brought repression under Saddam Hussein, when

seminaries were shuttered and scholars persecuted — over 300 clerics vanished

or were executed in the 1980s. However, the city endured, rising again in the

1991 Shiite uprising and, post-2003, reclaiming its spiritual stature in the

new Iraq.

The Sacred Pulse of the City

Najaf isn’t just a city, it’s a living shrine. Its social

structure reflects this sanctity in subtle and sometimes surprising ways.

Home to over 1.3 million residents as of 2024, the city is

predominantly Arab Shiite, but it doesn’t stop there. You’ll find Feyli Kurds,

Turkmen, Iranians, and students from as far as Nigeria and Indonesia. Many

internal migrants from Basra, Karbala, and Baghdad have also settled here, some

for faith, others for fortune or at least the promise of it.

And then there’s the Hawza — the heart of Najaf’s soul. An

ancient seminary system, the Hawza is less an institution and more an

intellectual ecosystem. Over 12,000 students from 40 countries studied here in

2024. They dive deep into jurisprudence, logic, philosophy, and theology. Some

even emerge as Mujtahids — high-ranking jurists with authority to interpret

religious law.

However, Najaf’s Hawza stands apart from its Iranian

counterpart in Qom. Where Qom supports the Iranian state’s model of clerical

rule, Najaf preaches quietism — the idea that religion should advise, not

govern.

This makes Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, who resides in

the city, a unique figure: immensely powerful, deeply revered, yet politically

hands-off. His influence helped shape modern Iraq, from guiding post-2003

elections to issuing the 2014 fatwa that mobilized millions against ISIS — all

without ever running for office.

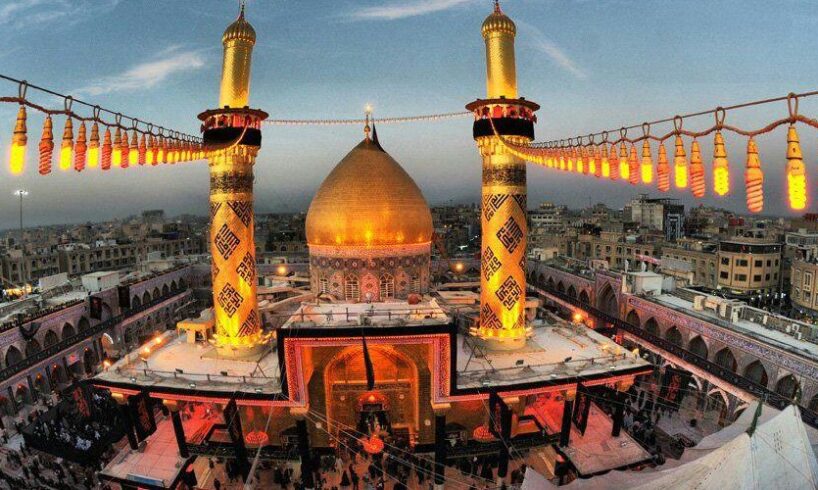

Between 12-18 million pilgrims visit the Imam Ali Shrine

each year. The shrine itself employs 15,000 people, further anchoring an

economic web of hotels (more than 2,000), restaurants, souvenir shops, and

local guides. Pilgrims walk for days just to touch the shrine’s golden doors,

leave a prayer, and take a photo that will sit on their wall for generations.

Pilgrimage in Najaf, however, is rarely confined to its

borders. Just 80 kilometers to the north lies Karbala, home to the shrine of

the third Shia Imam, Hussein, son of Imam Ali and martyr of the tragic Battle

of Karbala.

The connection between the two cities is not only

geographical but spiritual and emotional. During Muharram — especially on

Ashura and Arbaeen — millions of pilgrims traverse the road between Najaf and

Karbala, often on foot, in one of the largest annual peaceful gatherings in the

world.

In 2024, the Arbaeen pilgrimage drew over 22 million

visitors, many of whom began their journey in Najaf, touching Imam Ali’s tomb

before continuing to Karbala. The journey binds the memory of the father and

the son in one arc of devotion, grief, and hope.

Complementing the Imam Ali Shrine are other historic sites

that bolster the city’s role as a religious destination. The Mosque of Kufa,

just a short drive away, stands as one of the oldest and most significant

mosques in Islam. Built in the 7th century, it is believed to be the site where

Imam Ali delivered his sermons and where he was fatally struck during his

prayer.

Nearby, the shrines of Muslim ibn Aqeel, Hani ibn Urwa, and

Al-Mukhtar al-Thaqafi, all add further layers to Najaf’s sacred geography,

making the city and its surroundings a constellation of memory, martyrdom, and

reverence.

Grit, Grace, and Growing Pains

Najaf wears its holiness proudly, but like all cities, it

wrestles with real-world grit.

The economy, while supported by pilgrimage and religious

endowments (waqf), suffers from underemployment and fragility. Outside the

shrine sector, job options are limited. Many residents rely on daily wages that

fluctuate with the religious calendar. A pandemic or geopolitical hiccup can

shut down pilgrimages and send thousands scrambling for income.

On the edge of the city, agriculture hangs by a thread. Once

rich with date palms, barley, and wheat, Najaf’s farms now suffer from saline

soils and water shortages. By 2023, agricultural output had dropped to less

than 25% of historical averages. The land is tired, the rivers have shrunk, and

tractors sit idle while youth dream of emigrating to Istanbul, London, or

anywhere with Wi-Fi and a salary.

Urban development has also boomed, but not always in the

right way. Roads are battered, electricity comes and goes, while reliable water

is a luxury. A 2024 municipal report showed that 62% of Najaf’s neighborhoods

face chronic infrastructure deficits. Meanwhile, real estate prices near the

shrine have skyrocketed, while outer areas are neglected.

The University of Kufa, with over 20,000 students, offers

degrees in medicine, engineering, and the humanities. Women are present and

ambitious, though societal expectations often press pause on their careers.

Additionally, vocational schools and private institutions are growing, but many

students still opt for the Hawza, trading secular success for spiritual

scholarship.

Culturally, Najaf is a paradox: it’s rich in heritage but

reserved in expression. You won’t find modern art galleries or film festivals

here, but you will find thousands gathered to hear a poem mourning Karbala.

Religious theatres thrive, especially during Muharram, and

elegiac poetry (latmiyyat) resonates through the Hussainiyat. The city’s

libraries even house over 32,000 rare manuscripts, many untouched by modern

cataloging.

Whispering Power

Since 2003, Najaf’s clerical leadership has nudged Iraq

toward democracy, unity, and restraint. Ayatollah al-Sistani’s statements,

often issued through a spokesperson or carefully written communique, have had

more impact than any parliamentary vote.

Then there’s Muqtada al-Sadr, the unpredictable

cleric-populist whose base adores him but whose methods often perplex Najaf’s

quietist elite. In 2019, protests erupted in Najaf, culminating in the burning

of the Iranian consulate. Clerics urged calm, but the message was clear:

Najaf’s youth want jobs, dignity, and a future.

Each year, thousands of seminary students arrive from

Pakistan, India, East Africa, and the Gulf. These students return as preachers,

scholars, and spiritual guides, spreading Najaf’s teachings to far-flung

communities. In 2023 alone, over 5,000 international students were registered

in the Hawza.

But perhaps Najaf’s most important export is its moral

framework: that faith can inspire, restrain, and elevate. A lesson that, in

today’s world, feels more precious than ever.

Najaf isn’t flashy; it’s not built for selfies, yet it’s

unforgettable. For pilgrims, it’s a destination. For scholars, a sanctuary. For

locals, it’s just home — sometimes hard, always holy, forever theirs.

And for visitors brave enough to look past the dust and into

the heart of it, Najaf offers something deeper: not just history, but humanity.

Not just reverence, but resilience. Not just a city, but a story. One still

being written…

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.