The air raid sirens of Kyiv rise and fall, somewhat weaker than those of Tel Aviv. The distant noise allows for speculation in the opening seconds, whether it might not be an ambulance passing from a distance. Two young women, girlfriends, walk on the main street of the historic “Podil” neighborhood on the banks of the Dnieper River, crossing the city. They hold simple cardboard signs with scrawled protest slogans. “Are those sirens?” I ask. They giggle, check their phones, and determine there’s no danger – “It’s just drones.”

The time is about 11:30 p.m., and I have another half hour left to reach the hotel before the nighttime curfew, which will last until 5:00 a.m., goes into effect. Police deploy at street corners in preparation, and bars close one after another. I’m running late to return, and the entrance security guard clarifies this to me with a string of “blessings” whose meaning is clear even for a broken Russian speaker like myself.

Is the war that started three and a half years ago felt in Kyiv? For the foreign eye, certainly. Just on the last day of July, 31 people were killed in the capital from a Russian attack on it, 28 of them when a missile struck a residential building. In a central square facing the golden-domed monastery of Saint Michael the Archangel, burned Russian armored vehicles are positioned – this is a changing exhibition, according to supplies arriving from the front. Exhausted reservists wait at bus stations.

On the monastery’s long wall appear photographs of those fallen in the campaign. Some of the men in their official uniforms, others documented in less official episodes – those photographed by soldiers after a night of activity, when signing for receipt of new weapons and hurrying to document in the armory courtyard. Children of the 1970s, alongside youth born in the 2000s. Memory muscles from Tel Aviv help understand Kyiv.

War is one of the fundamental phenomena of human life. Contrary to what is proper, perhaps. It is so “natural” that it sometimes appears like a natural disaster – an earthquake, flood, or fire. Every long war is different, yet human in its manner. Heavy heat descended on Kyiv during my visit; here, too, memory muscles from Tel Aviv were helpful.

The wall featuring photographs of those fallen (Photo: AP)

A long war resembles a scorching sun, and the people marching beneath it cast their shadows in the streets of Kyiv and Tel Aviv. And it is different, like the responses to challenges it presents. “Oleg,” Olena, Roma, and “Cyclops” have been marching under its shadow for years. They are part of the story of this city, the nation, and the great war in Europe since World War II.

Buzzing creatures in the skies

“I didn’t know anything about drones. My first drone was a Russian drone,” Cyclops recounts when I meet him at a cafe a short distance from the city center. “A Russian column was destroyed from the air, and then we were in a period of partisan fighting. We needed weapons, and we reached the place. That’s how I found the first drone, a simple ‘Mavic’ [a popular commercial drone manufactured in China].”

Cyclops wasn’t near Kyiv when the war erupted. He originally hails from Odesa, the major port city on the Black Sea shore. “The day before the invasion, we already understood something was happening. My girlfriend and I decided to move to Mykolaiv; we thought it would be safe there,” Cyclops reconstructs the fateful days of February 2022. “There was chaos. The army wasn’t in the region. A truck arrived and distributed rifles, without registration, without anything.” He describes two months of “Wild West” and complete chaos, as he and his friends attempt to “knock down” Russian reconnaissance forces.

After more than two years on the front, he now instructs in advanced drone operation courses. The nickname? “My commander called me that because of the drone camera that resembles a Cyclops eye.” A name – like here – there’s nothing stronger than a nickname your commander gave you.

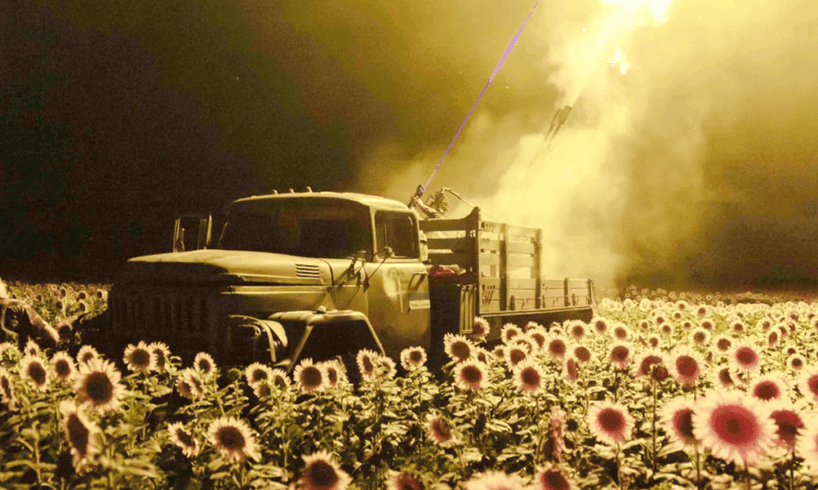

In the front of warfare, battle has become drone warfare. At least 70% of casualties in combat are attributed to their operation. Fighting trenches, storm attacks, and armored vehicles adorned with iron plates remind one of World War I battles, while buzzing “creatures” make reputations in the fighting armies.

In the latest development, drones operated through dedicated goggles providing a first-person flight experience (FPV) have been joined to optical fibers. This simple development, reminiscent of older technology, enables a drone that unfolds the wire behind it according to its flight to overcome radio interference and range limitations. Kilometers upon kilometers of thin and glinting wires cover the killing fields of eastern, southern, and northeastern Ukraine. This development is making reputations in front positions, but it is particularly lethal for supply routes. The war is becoming more difficult.

The way war is photographed has also changed. Suicide drones, those that explode upon impact, now provide documentation of the final moments of soldiers – Russians and Ukrainians alike. They are seen there fleeing in terror, accepting their fate in submission, pleading for their lives before the camera.

Within the war, Cyclops has already transformed into part of an official drone unit. “A drone company is constructed from about 30 people,” he explains. “It contains several teams of each capability type – ‘regular’ drones, FPV, and large supply drones. Usually, we position ourselves in a house, at a distance of several kilometers from the front.”

Cyclops operates a drone (Photo: Ojack Mariya York)

Cyclops describes a typical shift: “At night, you conduct about 15-20 attacks. It’s different compared to when you kill a person with a rifle. It’s much closer and you can see these people. In drones, it’s like video; in a thermal camera, you don’t see faces.”

Drone operators have become one of the most important targets for attack, and both sides do everything to find their positions. “I know one guy who sat three months alone, and food and water reached him only by drones,” he demonstrates how much forces in the field seek to avoid exposure and how much they’re willing to pay to achieve it.

Ukraine’s situation on the front is not simple, to put it mildly. Kyiv conducts an exhausting war of attrition against the Russian war machine, powered by Russia’s energy economy, fed by hundreds of thousands of men from prisons, from Russia’s social and geographic periphery, and from North Korea – sent as cannon fodder to storm Ukrainian trenches.

The British Ministry of Defense estimated the number of Russian casualties (killed, wounded, and captured) at more than one million, and assessments by research institutes and intelligence bodies specify a figure of up to about 250,000 dead. Russia’s sure and frighteningly slow advance, while bleeding heavily, creates pessimism in Ukraine and among its allies.

Cyclops believes victory is possible, and argues it depends on establishing a “wall of drones,” as he defines it. “We must try to stop at a certain line. Just stand in place, prevent Ukrainian casualties, and conduct drone warfare.” The logic is based on the assumption that attrition will finally defeat Putin’s regime and his army. What will he do after the war? He’s already thinking less about a military career; fatigue is showing its signs. “Like after a mission at the front – shower, good sleep for a few weeks or months – and life,” he says.

Protests against corruption

During my visit to the city, the first major political protest during the war broke out. This happened following lightning legislation – approved within a few hours – that President Volodymyr Zelenskyy led against independent anti-corruption bodies established at the West’s demand. Zelenskyy claimed he was fighting Russian influence and espionage that had spread in these bodies, but the move was seen as a blatant and undemocratic takeover attempt.

The Ukrainian people, who had already toppled a series of leaders through the streets, again took to the streets. They didn’t need a grace period to remove the “civic” rust that might have appeared as a result of the war. While the law was passed, hundreds of young people appeared in a small square in the city holding simple cardboard signs. Among the protesters was also a young man with an amputated leg.

The protest atmosphere is felt the moment I enter the metro. While waiting on the platform, I ask a young man how to get to a certain station, and he immediately wonders if I’m on my way to the demonstration. “I want to see it,” he says and admits he hasn’t yet decided whether he’s for or against the protest – “The situation is complicated.” Oleg, a young man in his 20s dressed in modern clothing, and his girlfriend Maria accompany me to the protest center.

As we approach, the demonstration atmosphere floods the streets. Roars of “veto na zakon” (veto the law) mix with calls of “hanba-hanba-hanba” (which might be more familiar to the Israeli ear as “shame-shame-shame”). The enormous resources the war demands, in no small part also from Western countries, are fertile ground for corruption of every kind. The protesters make an explicit connection when they shout, “corruption kills.”

“I think we were wrong to think a year ago that we could win this completely. We thought we had cards,” Oleg tells me up the street, a reference to that meeting between Zelenskyy and Trump when the American president threw at Zelenskyy that he “has no cards” to continue the war. Another protester hints that Zelenskyy’s move was intended to “derail the talks with Russia” that were taking place that same day.

At a certain point, singing of the Ukrainian anthem begins and intensifies. The strongest that evening. Some protesters will stay here throughout the night to thumb their noses at the curfew. Two days later, Zelenskyy will approve legislation that will restore independence to the anti-corruption bodies. There’s no place that better marks Ukraine’s independence, first of all from Russia and its customs, than its squares. And these young people and their predecessors.

Protest in Kyiv (Photo: AP)

“I remember life before”

Kyiv lives. I try to pinpoint exactly how the war is both absent and present in its life. Parties are held here even at night, in its basements, and celebrants emerge from them in the morning, heralding the end of the curfew. Businesses and cafes – all open. You’re asked in them if you want to donate to some unit at the front. Here, I sit, and across from me passes the funeral of a senior commander. His unit’s men march in dress uniforms behind the hearse carrying his coffin. I stand with passersby, some kneeling. The convoy passes, and the city continues on.

The marchers turn down the street toward Maidan Square – the central square where the banner of rebellion against the Russians was raised in 2014, which led to the uprising of Moscow-backed separatists in the east and the swift conquest of the Crimean Peninsula. The “Revolution of Dignity” then demanded to continue on the path of integration with the European Union. The blue flag with stars, which in parts of European populism is seen as abhorrent, is still a sign of freedom.

Since the war began, Maidan has become a kind of cemetery. It’s dedicated to a forest of Ukrainian flags, its military units, and flags of the countries of volunteers who fell here. Under the flags – photographs of the fallen. Perhaps that’s why the protesters didn’t return to this square, which now serves a different role. Perhaps they signaled that they don’t deny the legitimacy of the government conducting a war for the nation’s life.

I met Olena Maksimenko at one of the city’s cafes. The war – and forgetting it – interweave in the capital’s streets. She herself experienced two such waves, of war and forgetting. Once, when she was kidnapped and tortured by the Russians during the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the Donbas war that followed, and a second time now, after the full Russian invasion in 2022.

“I remember life before – those were quite different lives,” she sighs. After her release from Russian captivity in 2014, Olena volunteered in a small volunteer unit dealing with treating the wounded. “The government didn’t give money, we lived on private donations,” she explains the necessity that turned her into a war correspondent. “And to get donations, you need to tell stories.”

Until 2022, routine made the Ukrainian public forget about the war being conducted in the east before the war. All the more so from the world’s attention, which was then still far from full adoption of Kyiv’s struggle. “There was indifference,” she describes, “it’s hard to write for no one.” She sought her way and interviewed for a magazine (“something between advertising and media”), but then the Russian invasion began. “I understood I must stay until victory.”

Olena Maksimenko

Olena is part of what can be described as the “Ukrainian war community” – even within a nation fighting for its life, there are those who bear the burden more than others. Those captivated by it, by its purpose, and perhaps – and it’s hard to say this – by the charm of meaning, of evil, of gazing into the consuming fire.

“In my circle, everyone is very active and involved,” Olena says, “but these are mainly volunteers, war correspondents, or family members waiting for news from someone on the front line.” The stories from the front she collected in her book “Priama Mova” – a concept that can refer both to bringing things in first person, and to open and sometimes blunt speech.

But the long war creates problems that this small community cannot solve. It’s hard to estimate the number of Ukrainian casualties, when the UAlosses project counts about 80,000 verified dead. The need for fighters places a heavy burden on Ukrainian society, and this is perhaps the most burning issue here.

Ukrainian conscription policy refuses to forcibly draft those under age 25, out of concern for losing the generation destined to be the one that will rebuild the country, and out of deep demographic worry. Up to age 60, everyone is obligated to serve, and they’re also banned from leaving the country. Exemptions are given to fathers of more than three children, to students, and to those with needed professions.

Three and a half years later, the stream of voluntary enlistees is dwindling. “Blue” and “green” police are deployed in Kyiv’s and other cities’ streets, trying to extract from the street those who didn’t report voluntarily. From time to time, videos of violent arrests are circulated. The pressure all this exerts on society is enormous.

Only a black swan will help

Eduard Dux, an Israeli-Ukrainian journalist who previously worked in tour guidance – an occupation now rare on Ukrainian streets – reports on emerging wartime dynamics. He describes Telegram groups that track locations of military recruitment officers, enabling draft avoidance. Additionally, he documents cases such as a factory owner who reduced merchandise packaging sizes specifically to hire more women, compensating for acute male labor shortages.

“Those same men remain on the front line,” Olena describes the unbearable situation, “and everyone understands this problem. But they say, ‘I can’t leave my guys, I can’t leave my position. I’ll fight on one leg, but I’ll stay.'” At the same time, she says, “there the people are always eager. They don’t have time for reflections on the situation, for crying. They have missions and a short time for rest.”

This situation creates growing social tension. “We have a gap in society between military people and civilians,” she explains. “They get angry when they see men in city centers, while they’re at the front, and these guys are drinking beer in bars.”

Zelenskyy’s false promises for a law that would enable the partial release of soldiers led to additional frustration. “Our government promised this law was almost ready,” Olena recalls angrily. “A week ago, someone asked Zelenskyy about the law, so he answered – ‘Oh, no-no, there will be no release before victory.’ How can we now take new people into the army when they don’t know when and if they’ll return?”

The criticism of Zelenskyy is sharper. “In my circle, 99% hated him before the elections, and they hate him now,” she says honestly. “He makes a lot of stupid decisions.” Olena describes two moments in the war when she felt respect for the president – when he stayed in Kyiv when the Russians invaded (“I need ammunition, not a ride” was his memorable quote), and when he confronted President Trump and his arrogant deputy JD Vance in the Oval Office, who attacked him on the conscription issue and received an answer that the US would also feel these problems if it were caught in war.

I ask her about the future and Ukraine’s chances. “The only thing I believe will help us is a black swan.” She means the situation in the campaign is so grim that it’s hard to imagine the event that could pull the cart out of the mud. The difficult moment in the war? “Maybe it’s now, right now. No one sees any reason for optimism.”

And still, Olena doesn’t believe in the need to reach an agreement with Putin. She simply thinks it has no value. “Zelenskyy is naive; maybe he really believes in the possibility of dialogue with the Russians. There can’t be an agreement, not because of us, but because of Putin. No agreements are possible except victory.”

Joking in the face of another shell

Despite these words, Zelenskyy still enjoys the support of most Ukrainian citizens. The latest survey by the International Institute of Sociology in Kyiv testifies to 58% trust in the president – a certain decline, but still a clear majority. But even so, and despite demands by presidents in Washington and Moscow to hold elections in the country to “get rid of” the stubborn Jew, no one I spoke with denied that elections cannot be held during wartime, given the constitutional ban on this.

Roma performs for Ukrainian soldiers (Photo: Courtesy)

I met with “Roma” in a Kyiv suburb, about a 40-minute drive from its center. He writes professionally, mainly comedy, and appears to have long ago crossed age 40. Before the war that devoured everything, he worked at Zelenskyy’s production company, from which his political party also grew. Zelenskyy, who was a comedian before becoming president, played the character of a history teacher who was elected to the presidency in a popular comedy series. “I saw him a few times, but didn’t speak with him personally,” Roma said.

When the war broke out, Roma was in Kyiv. His future wife was then with her son in another district, and he prepared for a regular workday. “I was supposed to meet a friend, drive to the office to write,” he recalls plans that evaporated at 4 a.m., when “we understood no one works anymore.” The decision came immediately – “I called her and said, ‘Don’t come here, I’m going to the army.'”

She decided to come anyway, expecting this would prevent him from fulfilling his decision. They spent one day together before he declared “That’s it, I’m going to the army.” He admits he “didn’t think it would last years.” In those days reality was chaotic. Enlistees were forced to purchase most of their equipment themselves and improvise protective gear. Before reaching the front, his training included firing one magazine of bullets.

He was assigned to one of the war’s hardest fronts. “Our mission was to stay in positions, hold them. If we retreat, they’ll approach,” he tells of the difficult battle days. “They shelled us 24 hours, we didn’t even shoot. We didn’t see anyone, just took beatings. Our mission was to live.”

Two years he lived like this. He tells of the difficult first winter, of friends who died and of long watches. But also of humor – “Without jokes it was impossible to survive. When a shell flew over us, we joked.”

In the last year he moved to a morale position, providing psychological support and comedy shows for soldiers. “I’m a soldier who went through battles, and I speak with them in the same language.” Last May an old hand injury – worsened because of shell impact – led to his discharge from the army. “Almost three and a half years,” he summarizes.

Now he’s returned to writing. He tells me, as we sit in a hookah bar restaurant(!) in the closed and beautiful neighborhood, that he’s writing a series, a kind of Ukrainian version of “Fauda,” and hopes to sell it to Netflix. About the Israeli series, he says – “What I loved is that there’s no bad person there. Everyone does their job, everyone defends – the Israelis theirs, the Palestinians theirs. Everyone is right about something.”

But Roma, who experienced war up close, reaches hard conclusions about the future. “It seems to me this can continue a long time. If the international community doesn’t pressure Russia, it will continue forever. Russia has resources for 30 years. We won’t hold out.”

He recognizes the need for a diplomatic solution, and believes Zelenskyy can provide it. “Political decisions are needed. Zelenskyy made a decision not to talk with Putin. Now he’s already ready to talk with Putin. Everything changes, the situation changes, we need to be flexible.” He doesn’t fear criticism of his position – “They’ll tell me things, but I don’t care. I was there, I saw. We won’t defeat Russia by force. We don’t have enough weapons – you can fantasize someone will save us like in a scene in ‘The Hobbit,’ but it won’t happen.”

Sweet grandmother on the bus

In Kyiv, there’s no coming or going except through land transportation. Civil aviation in the country has been paralyzed since the full Russian invasion in February 2022. Those arriving in the city or leaving it are forced to do so via the route Moscow’s armor columns sought to pass, before being stopped in its suburbs due to the boldness of its defenders and the disorder of the invaders. Three years later, silent testimonies to that drama remain in place – iron crosses against tanks along the road (“Czech hedgehogs”), guard positions and camouflage nets, sandbags in government building windows.

For middle-class individuals, the journey abroad – and returning home for me – resembles somewhat a hasty escape, a refugee movement. To catch the flight from Chisinau in the afternoon hours, I board the 11:30 p.m. bus the day before. Beside me sits a sweet grandmother, in whom I see those who raised me, and a woman in her 30s traveling for vacation on the shores of Antalya.

How does one march under the scorching sun? It’s much simpler, apparently, than it seems. A person lifts his legs in life and doesn’t cease until he ceases. So too in war, from the moment you start, you march despite everything. It’s more natural than stopping and ceasing.

I hurry to the departure gate and feel a touch on my shoulder. The grandmother smiles at me, asking to say goodbye. “Have a good life and peace,” khoroshoy zhizni i mir, in Ukrainian. We part. Good life and peace.