Javier Milei strode onto the stage in Santiago, flung up his arms and gave a bow to an economist with a front-row seat: Rolf Lüders, one of the last of the original Chicago Boys.

That was in 2019, four years before Milei would win election to Argentina’s Presidency and start delivering his anarcho-capitalist style of shock therapy to one of Latin America’s most crisis-wracked countries. When the two men had huddled earlier that day, Lüders recalled, Milei eagerly soaked up the first-hand account of how a band of University of Chicago economists transformed Chile into a free-market blockbuster a half-century ago.

Lüders, 90, had a warning for Milei, one that’s often forgotten in an era of made-for-social-media politics, restive voters and fast-money global investors who can make or break a nation’s economy.

“Structural economic changes are complex,” he recalled in an interview late last month. “People don’t understand how much it cost to bring change here. It was a process that took years, not without big costs initially.”

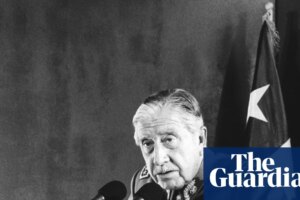

Implemented during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, the drastic reforms included massive spending cuts and the eradication of price controls following the rocky socialist tenure of Salvador Allende, who was toppled in a 1973 coup.

The market-based policies plunged Chile into painful recessions in 1975 and again in 1982. The second was caused in part by the effects of Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker’s aggressive fight against inflation (also guided by the theories of the University of Chicago’s Milton Friedman) that helped send Latin America into a slump so severe that the 1980s became known as “The Lost Decade.”

It was only after those painful recessions that Chile’s economic experiment ushered in decades of prosperity, allowing its per-capita income to leapfrog past Argentina, Brazil and Mexico.

After democracy returned in 1990, successive centre-left administrations went on to deepen the Chicago-inspired approach while layering on regulations and social programmes to give it a “human face.” Poverty rates plummeted, creating a robust middle class.

Now Milei, fresh off a comeback legislative-election victory that’s given him new political momentum, is striving to do something similar in Argentina, where layers of bureaucracy and spendthrift governments sowed runaway inflation and decades of crises.

But the market-based model professed by Lüders – often described as neoliberalism or, as he prefers to call it, a social market economy – requires a level of government support at odds with the slash-the-state libertarianism embodied by Milei’s chainsaw-wielding theatrics.

“There is an enormous difference,” Lüders told Bloomberg during an interview at his apartment in Santiago. “They are two different worlds.”

Libertarians, he said, want a free market with no state: “In reality, that’s not feasible.”

One of the first generation of Chileans to study at the University of Chicago in the 1950s, it was Lüders who invited Friedman to Chile in 1975, less than two years after Pinochet had seized power. It was also Lüders who arranged for the professor to meet with Pinochet.

After Friedman had pitched “shock treatment” for Chile, Lüders recalled, Pinochet “asked him to send his recommendations in writing.”

In his now-famous letter to the general, Friedman “refers approvingly to what was being implemented in Chile as a social market economy,” Lüders said.

Friedman’s recommendations for deep cuts in government spending and lower tariff barriers were followed almost to the letter a month later, years before Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom or Ronald Reagan in the US made their own neoliberal turns.

But what happened next may have influenced Lüders’s attitude toward modern-day libertarians. After an initial recession, Chile’s free-market reforms triggered a credit-fueled boom that ended in a devastating bust six years later.

Lüders was tapped by Pinochet in 1982 to pick up the pieces. He took over commercial banks, tightening regulations and tried to create what Pinochet wanted, a social market economy similar to Germany’s.

The result was the more cautious, state-managed version of neoliberalism that emerged from the crisis, engendering four decades of growth that turned Chile into the region’s star economy. Friedman liked to call it the “miracle of Chile.”

While the economy has performed sluggishly over the past decade, the fundamental legacy has endured. Even leftist millennial president Gabriel Boric, an Allende admirer who once vowed to turn Chile into the “tomb of neoliberalism,” has kept it largely intact.

Losing support

Milei is only just embarking on the long economic transformation that Chile underwent five decades ago. The shaggy-haired president has cut deeply into government spending and pulled annual inflation from nearly 300 percent to roughly one-tenth of that pace.

But there’s also been the type of state intervention that’s anathema to libertarians. The exchange rate on the peso is controlled to keep it in a narrow band with the dollar, which is the currency still favoured by Argentines burned by devaluations. Tariffs remain high.

When fears flared that Milei’s agenda would be derailed by the October 26 elections – causing investors and residents to dump the peso – Argentina turned to the Trump administration, which intervened in Buenos Aires’ markets to prop up the currency.

Yet as Milei considers ways to solidify his allies’ support, the Argentine leader contends with political challenges that weren’t faced by the dictatorship behind the transformation on the other side of the Andes that’s created a lasting free-market consensus.

“I don’t think we’re in a situation of great polarisation in terms of economics,” Lüders said.

In Lüders’ view, the economic debate in Chile is largely settled, which he said is illustrated by the generally broad agreement between the agendas of the three major contenders in the November 16 presidential election: the Communist candidate for the centre-left alliance, Jeannette Jara; centre-right candidate Evelyn Matthei, and arch-conservative José Antonio Kast.

“At heart, they are very similar,” he said of their economic programmes.

Lüders said he is leaning toward Kast, who is advocating for aggressive spending cuts, because he still thinks Chile would benefit from dialing back the size of the state.

“I’m optimistic about Chile’s economic future,” he said. “There is broad appreciation for economic growth and the country has the technical teams necessary to propose measures to bring it about.”

“No one wants to expropriate or fix the price for the guy selling vegetables on the corner anymore,” he said. “The battle in favour of a social market economy is won.”

by Philip Sanders & Patricia Garip, Bloomberg