Shafaq News

Once a defining

marker of identity and scholarship across the Arab world, Arabic handwriting is

now in steady decline. Teachers from Baghdad to Amman and Cairo say they

increasingly struggle to read student exam papers. Parents describe notebooks

filled with distorted letters and erratic lines. Education specialists warn

that the skill, which once anchored governance, literature, and religious

scholarship, is fading at a pace faster than educators can address.

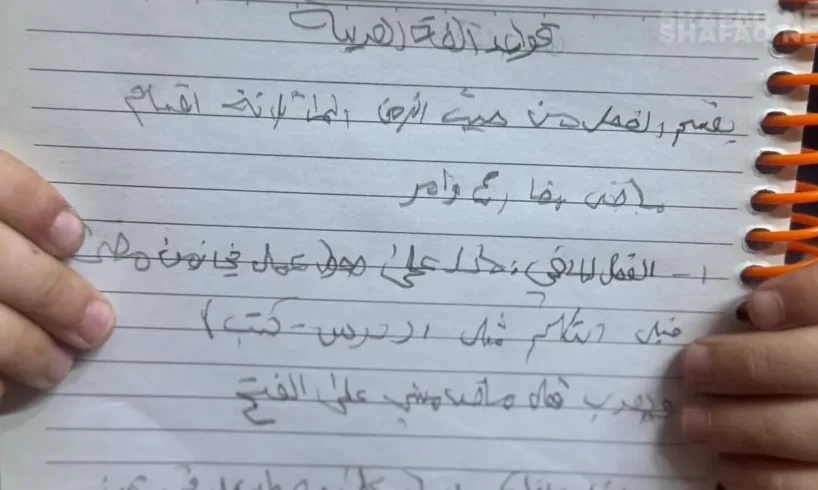

In Iraq, the signs of

this erosion are visible as early as the third and fourth grades. Students

themselves admit they no longer see handwriting as important. Ammar, a

fourth-grade student, said he memorizes information and writes it down during

exams just to pass, adding that no teacher has ever criticized his handwriting

and that grades remain his only priority. A third-grade student, Fatima,

described a similar experience: “I write exactly as I read in textbooks, and my

father draws long guiding lines across my notebook so I can keep my writing

straight.”

At home, the

challenge becomes even more visible. Rasha, a working mother in Beirut, spends

evenings guiding her nine-year-old daughter’s hand as it moves unevenly across

the page. She draws lines to help her write straight, yet the letters still

drift upward or compress into hurried shapes. The process is slow and

discouraging. She recalls a childhood in which “a neat page carried a sense of

pride,” and worries her daughter is losing not only a skill but a connection to

the language itself.

In southern Iraq,

Jamal has revived an old classroom practice by drawing horizontal guidelines on

blank pages for his son. The boy writes quickly and carelessly, and letters

collapse into one another. “My son types with impressive speed but struggles

with basic handwritten forms. Handwriting is a relationship with the language

that cannot be replicated on a screen,” he said, describing the broader erosion

of foundational skills.

Teachers say this

decline has been years in the making. Heavy Arabic curricula leave little room

for foundational drills such as letter formation. Instructors in early grades

focus on finishing the syllabus rather than correcting handwriting. Shortened

periods in double-shift schools make dedicated writing practice nearly

impossible, while many households facing economic pressures no longer supervise

handwriting at home.

These issues converge

with factors inside the classroom. Several educators admit that newly recruited

teachers sometimes struggle to form letters correctly themselves.

Teacher-training institutions have leaned heavily toward technology-based

pedagogy and exam-oriented methods at the expense of script instruction. The

disappearance of the dotted handwriting booklet—once essential in early Arabic

literacy—has further removed a tool that allowed children to trace letters and

internalize proper structure.

Here, educators

emphasize that the decline is not only structural but behavioral. An

Arabic-language professor, Naif Shalal al-Khalidi, attributes part of the

deterioration to reduced writing frequency and the growing use of computers and

mobile phones instead of pens. He also notes a lack of motivation among

students to improve their handwriting and weak parental follow-up. “The problem

is compounded by inconsistent classroom attention and the absence of positive

reinforcement.” In his view, systematic training workshops, competitions, and

incentives could help revive student interest and restore handwriting as a

valued skill.

Regional educational

reports show that handwriting challenges extend far beyond Iraq. Surveys

conducted in several Arab states indicate widespread difficulty in reading students’

written responses and gaps in teacher preparation in teaching handwriting.

These trends coincide with the rapid expansion of smartphones, tablets, and

digital communication, reshaping how young people interact with text.

Salem Habib, a

handwriting specialist, said multiple studies found that children who rely

primarily on typing show weaker activation in brain areas responsible for

visual memory and language retention. “This is particularly significant for

Arabic, a script built on continuous hand movement and visual-spatial

coordination,” Habib noted that prolonged use of devices reduces fine-motor

control and visual sensitivity to letter shapes, making it harder for students

to regulate pen pressure and maintain proportion.

For centuries,

handwritten Arabic served as the vessel of intellectual and cultural life—used

in religious manuscripts, scientific works, poetry, and governance. Scripts

like Kufic, Naskh, Thuluth, and Ruq‘ah shaped the visual identity of the

region. During colonial periods in North Africa and the Levant, handwritten

Arabic was preserved in homes and community mosques, functioning as a subtle

form of cultural resistance.

Today, handwriting’s

symbolic value remains intact, but its educational foundations continue to

erode. Linguistics professor Ismail Hanna attributes the decline to weak

writing habits, digital reliance, limited motivation, and insufficient

follow-up from teachers and parents. “Handwriting cannot recover without

consistent monitoring, encouragement, and structured practice,” he stressed.

Other specialists

point to how script choice itself affects learning. For many students, early

education now relies heavily on Naskh—a formal script similar to Qur’anic

writing. At the Institute of Fine Arts in Dhi Qar, instructor Salah al-Din

al-Jassem argued that this slows learning because Naskh requires more precision

and longer training. He believed Ruq‘ah, traditionally used for everyday

writing due to its speed and simplicity, “is a better pedagogical starting

point but has gradually disappeared from early curricula.”

Al-Jassem traced part

of the decline to rapid digitalization and changing student attitudes. “The

dominance of keyboards and screens has overshadowed penmanship and weakened the

psychological readiness of students to engage in slow, disciplined handwriting

practice.” He noted that handwriting once relied on Ruq‘ah-based practice

booklets widely used in the 1950s, but that today’s early-grade teachers often

lack structured exercises and repetition techniques that help children

internalize correct letter shapes.

According to Jassem,

students must develop visual-motor skills, not only in drawing letters but in

imagining them. “Letter formation begins with a visual image,” he explained,

adding that proper posture, seating, and grip are essential. Teachers, he says,

must monitor hand-eye coordination closely during writing to reinforce correct

technique.

Across the region,

countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Lebanon have reintroduced Ruq‘ah

in primary curricula or reinstated handwriting booklets in private schools.

Morocco and Tunisia maintain relatively strong handwriting outcomes, partly due

to smaller class sizes and earlier script instruction.

Iraq, however, faces

additional obstacles. Overcrowded classrooms, curriculum overload, inconsistent

teacher preparation, and limited time in double-shift schools make sustainable

reform difficult. Examination committees increasingly report concerns about

illegible handwriting affecting the fairness of assessments, particularly in

subjects requiring extended written responses.

Despite these

challenges, Hanna pointed out that research repeatedly shows that handwriting

practice strengthens reading comprehension, cognitive processing, and long-term

retention. “Students who regularly write by hand develop stronger connections

between letter shape, sound, and meaning, an advantage that is especially

important in Arabic.”

Reform, however,

requires more than classroom adjustments. “Restoring handwriting demands a

coordinated effort,” Hanna said, “from strengthening teacher preparation to

reintroducing structured handwriting curricula and reinstating practical tools

like dotted handwriting booklets.”

Digital instruction,

according to him, must be balanced with traditional writing practice, and

cultural institutions can help connect younger generations with script

traditions through hybrid calligraphy-and-design programs.

The skill that once

underpinned Arabic thought, identity, and scholarly life is now at risk.

“Rebuilding it will require far more than longer lessons or revised booklets.

It will require restoring a cultural relationship with the written word—one

that shaped Arab societies for more than a millennium,” he concluded.

Written and edited by

Shafaq News staff.